A building block of proteins found in samples from an icy comet’s halo suggests that the ingredients of life could have hitched a ride to early Earth, researchers reported August 16 at a meeting of the American Chemical Society.

“The early Earth was bombarded with comets and meteorites,” says Jamie Elsila of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., who led the new analysis. “This is one more clue to what ingredients could have been present on the early Earth and how they could have gotten there.”

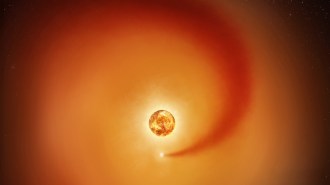

NASA’s Stardust spacecraft collected the study samples when it flew through the gassy halo, or coma, of the comet Wild 2 (pronounced “Vilt-2”) in 2004. Two years later the collecting device parachuted to Earth, landing in the dark of night in Utah. Previous analyses by Elsila’s NASA colleagues Daniel Glavin and Jason Dworkin revealed that the samples contained amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. Proteins are the major construction material of living things and many are tasked with making fundamental biochemical reactions happen. But the analyses couldn’t rule out contamination by earthly proteins.

Now finer instruments reveal that samples of glycine, the smallest amino acid, are indeed extraterrestrial. Glycine molecules in the comet samples contain more of the heavy version, or isotope, of carbon than earthly glycine has, Elsila reported. A paper describing the discovery has been accepted for publication in the journal Meteoritics and Planetary Science.

“This is a really nice confirmation,” says Ralf I. Kaiser, a physical chemist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and NASA’s Astrobiology Institute. Lab studies by Kaiser and others have shown how energy from UV light or solar winds could spur the formation of amino acids in space. Galactic cosmic rays can penetrate meters deep into ice, says Kaiser, suggesting that other amino acids could form inside a comet’s icy body.

The find is “very pleasing and satisfying, but not a shock,” says Elsila. While previous reported detections of glycine in interstellar space have been disputed, plenty of amino acids have been detected in meteorites and amino acid precursors have been found in comets. Wild 2 is thought to be a very old comet and it could provide a snapshot of what was around when the solar system formed, Elsila says.

Glycine is small and volatilizes easily, facilitating its detection in the comet’s gassy halo. Probing the innards of a comet may reveal even more of life’s molecules. The European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft is scheduled to release a small lander on the icy nucleus of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in 2014.

“I’d be very interested in a comet nucleus,” says Elsila.

View Dust to dust from Science News on Vimeo.