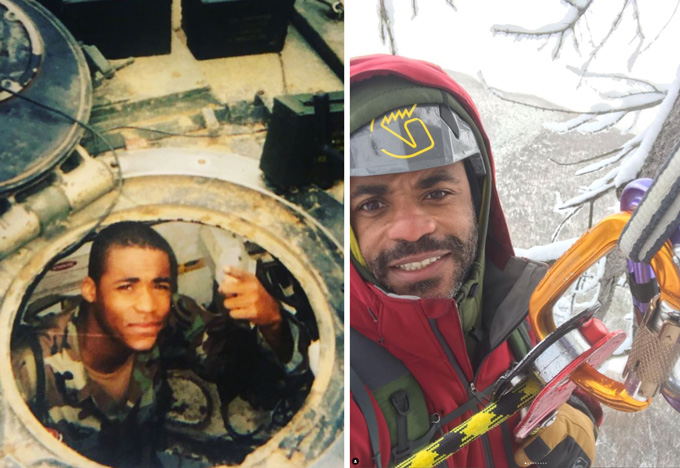

Demond Mullins climbed Everest to inspire more Black outdoor enthusiasts

The sociologist also studied how outdoor adventures help veterans build social bonds

On May 12, seven members of Full Circle Everest, an all-Black mountaineering team, reached the summit of Mount Everest.

The North Face, Full Circle Everest

Demond “Dom” Mullins’ days as a student at Lehman College in New York were interrupted in 2004 when his National Guard unit was deployed to Baghdad. A year later, he returned home but struggled with depression and rage. Immersing himself in his studies helped him make sense of the world and his experiences. After completing degrees in Africana studies and political science, Mullins earned a Ph.D. in sociology, focusing his research on a subject he knew firsthand: how returning veterans reintegrate into society.

In 2015, the avid climber and adventure sportsman joined six other veterans and a journalist on a monthlong excursion to climb Alaska’s Denali, the highest peak in North America. To understand the health benefits of high-risk outdoor adventuring outside the clinical therapy framework, Mullins interviewed each participant and collected data about group cohesion and the impact of such high-risk activities on social bonds for his study “Veterans Expeditions: Tapping the great outdoors.”

Formerly an adjunct assistant professor at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York City, Mullins has climbed Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya. In May, he tackled his biggest climbing challenge yet: summiting Mount Everest, the world’s tallest mountain. He and seven other members of Full Circle Everest, an all-Black mountaineering team, set out to make history. Seven of them reached the summit, coming very close to doubling the number of Black people who have achieved that feat.

Science News asked Mullins, while he was preparing for the climb, about his research and why he wants more Black people in outdoor spaces. This interview was edited for clarity and length.

SN: When you returned home from Iraq, you cut yourself off from others and contemplated ending your life. What helped you get through the worst times?

Mullins: Education. I was grappling with the discontents of coming home and struggling with what I had experienced in the Iraq War. Education allowed me to explore aspects of my experience intellectually through things that really engaged me — history and social theory.

SN: Did the war change what you envisioned for yourself academically?

Mullins: It influenced my trajectory. Graduate school was not even on my radar before. When I came home, I had this great urgency to improve my future, learn more about global politics and understand how history could produce such a moment. I also wanted to know how all of that might influence veterans’ reintegration.

SN: How did the Denali research expedition follow on your work on veteran reintegration?

I became an avid mountaineer, rock and ice climber and began training with Veterans Expeditions [a nonprofit that works to enhance the life of U.S. veterans]. By the time the Denali expedition came about in May 2015, the cofounder [Nick Watson] asked me to be a part of it. I wanted to tell the story of veterans summiting Denali in a way that makes sense, was scientifically rigorous and could contribute to the research. I wanted to answer certain questions about how interventions like hiking and climbing might come into play. Ethnography [the study of people in their environment] was the best way to do that.

SN: What did you learn about veterans and outdoor adventuring?

Mullins: Much more than in the past, my generation of veterans is more willing to talk about their experiences with each other to find affinity and solidarity. After leaving the service, some lose their identity, partly because there is no space reserved for them to perform the identities they have cultivated through military training, socialization and performance. I learned that they engage in these kinds of high-risk sporting events to support their identities. The outdoors is sort of a theater to perform the heroic identities they’ve developed in a way that can be conducive to greater physical and communal health. One veteran said to me, “The rock and the ice don’t lie to me.” He was reasserting that he is a warrior.

SN: How did you become a part of Full Circle Everest?

Mullins: Through Veterans Expeditions, I developed a relationship with [world-famous mountaineer] Conrad Anker. Conrad had this idea about putting together an all-Black expedition to Everest. He introduced me to [Full Circle expedition leader and organizer] Philip Henderson, who had been considering this for a long time. I met Phil and knew right away that I wanted to be a part of that expedition and help find other athletes.

SN: What, if anything, about your experience on Denali do you believe will benefit your attempt to summit Mount Everest?

Mullins: Everest is 9,000 feet taller than Denali. It’s a longer pursuit and a longer expedition, but the conditions will be similar. We got snowed in on Denali for 17 days, which I believe has prepared me for my expedition with Full Circle.

This pursuit is about developing relationships with people who have common experiences. It’s having someone who gets your drift, who understands what you mean without you needing to explain everything. It’s about building community and feeling like you belong. People want to feel like the group is better as a result of their participation. It’s all about social cohesion.

SN: Will you be conducting research on this expedition?

Mullins: This time, I’ll be studying myself — doing an autoethnography. I took time off from work to do this climb, so I don’t have any pressing job to get back to. I plan to take some time to reflect and write about this once it’s over, to help people understand the value of it for me.

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

SN: The Full Circle team spent a few weeks together in January at the Khumbu Climbing Center in Nepal. Your teammates went home, then came back in April to start the climb, but you stayed in Nepal. Why?

Mullins: It gives me an edge in so many different ways: having time for my body to properly acclimate to the elevation, understanding how to keep myself safe and comfortable in the elements. Also developing relationships with the locals, the Sherpas and the other Nepalese persons who are supporting the expedition.

SN: What do you want people to take away from your Full Circle Everest expedition?

Mullins: Diversity in the outdoors matters. The military completely introduced me to outdoor sports. When I was a kid, I never went camping or even hiking. I thought [Brooklyn’s] Prospect Park was the wilderness. These activities have benefits for all people. Hopefully, Full Circle will help African Americans of all ages get outside to hike, camp and explore.