A toxic gas that could help spawn life has been found on Enceladus

The moon’s water plume contains hydrogen cyanide, an analysis of Cassini data suggests

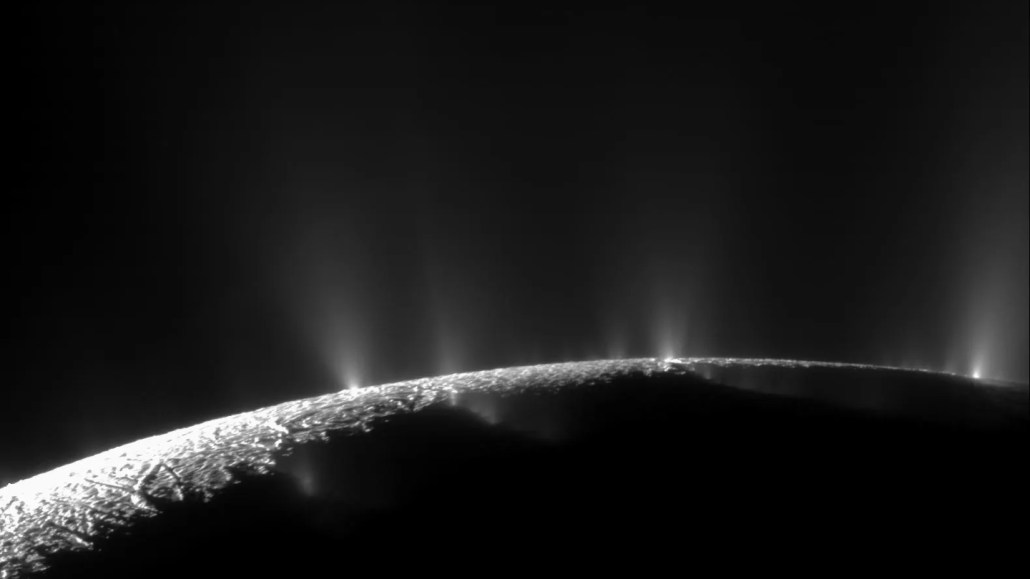

In 2005, Cassini discovered jets of water (shown) erupting from Enceladus’ surface. The spacecraft later flew through the plume of material formed by the jets multiple times, measuring the plume’s composition and detecting chemical ingredients for life.

JPL-Caltech/NASA, SSI