If he were starring in a campy horror flick, Tim Rowbotham might have gasped and whispered, “It’s alive!” As a microbiologist with Britain’s Public Health Laboratory Service, he had isolated an unknown microorganism from an amoeba growing in a water tower in Bradford, England. Rowbotham baptized the entity “Bradford coccus.” He added his new specimen to the collection of bacteria that live within amoebas and continued the search for the cause of a pneumonia outbreak plaguing the citizens of Bradford.

But Rowbotham hadn’t discovered a bacterium. He had actually found a gigantic virus—one so large and possessing such a peculiar mixture of traits that it is challenging the very notion of what it means to be alive.

Viruses have long been regarded as nonliving entities. They don’t have the machinery to make new viruses, nor do they have a discernible metabolism (you won’t hear a virus declare “as I live and breathe,” and not just because they don’t have mouths). Viruses are typically thought to barely have genetic material to call their own, characterized instead as ghostly gene-thieves who prey upon and steal from real organisms. But as scientists shine the spotlight on the shadow economy of the virus world, a new vision of viruses is emerging. Rather than furtive thieves, viruses are more like commodities dealers, playing a major role in transferring genes from one organism to another. The acquisition of new genes may dramatically alter the lifestyle of the organism that gets the goods, allowing it to invade a new environment, for example, or fight off predators.

Viruses also may keep genes they’ve procured, and even bundle these assets together, as appears to be the case with several photosynthesis genes recently found in marine viruses. These finds hint at the vast viral contribution to the ocean’s gross national product and viruses’ significance in global energy production.

“Viruses are major drivers of nutrient and energy cycles on the planet,” says marine virologist Curtis Suttle of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

This increased appreciation of the viral influence on cellular life today is reviving debate about the role viruses may have played in the planet’s primordial days, scientists say. Viruses may even be at the root of the cellular tree of life, participating in the evolution of the eukaryotic nucleus.

“Viruses are and have been a main force in the evolution of life on the planet,” says Jean-Michel Claverie of the Mediterranean Institute of Microbiology in Marseille, France. “They remain a leading force in the cellular world.”

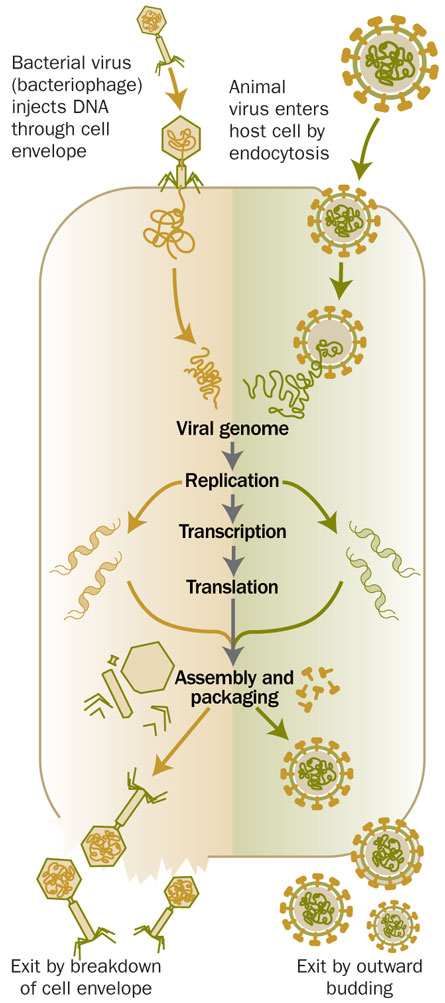

Of course, part of that force is virus as bad guy. From the common cold to influenza to Ebola, viruses have long been recognized as agents of illness and death. Viruses infect all domains of life—from plants and animals to protists and bacteria. In fact, viruses lurk behind many ailments blamed on bacteria. For example, the bacterium that causes diphtheria does so only when it carries a virus.

Scientists have long been well acquainted with the nefarious activities of these viruses of doom, but now a more productive view of death by virus is emerging. Viruses don’t just kill plants and animals—they kill the organisms at the bottom of the food chain, deaths that have dramatic implications. “If you take viruses out of seawater, counterintuitively, things stop growing,” Suttle says. In death, victims of viruses release nutrients. “Their killing feeds the world.”

White cliffs of death

Viruses are the most numerous entities of the oceans; a thimbleful of seawater contains millions of virus particles. Stretched end to end, the estimated 1030 viruses in the oceans would reach farther than the nearest 60 galaxies, Suttle notes. These viruses infect creatures from krill to whales, sometimes with worrisome effects, as with the one that spurs tumor development in green sea turtles. Viruses also infect phytoplankton—the microorganisms that include algae and photosynthesizing bacteria. These tiny critters are the major force behind the ocean’s nutrient and energy cycles and make up about 90 percent of the oceans’ biomass. Viruses kill an estimated 20 percent of this biomass every day. (Fortunately, phytoplankton are avid propagators and replenish themselves quickly.)

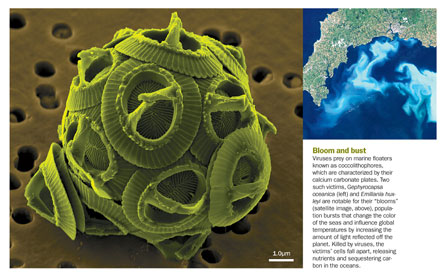

In the long term, this death on the high seas can shape the land, as it did with coccolithophores, single-celled marine floaters known for their calcium carbonate skeletons. Those skeletons eventually became the layers of rock known as the chalk group, outcrops laid down in the Cretaceous.

“The white cliffs of Dover are 100 percent the cytoskeleton of those animals,” says Claverie. “Those animals were killed by viruses.”

Oceans teem with coccolithophores; their “blooms” turn the seas a milky blue and then quickly dissipate—a boom-and-bust cycle now linked to marine viruses. Not only do these deaths influence the makeup of the marine microbial community, but they also affect geochemical cycling. As these dead phytoplankton sink in the seas, they sequester an estimated 3 metric gigatons of carbon each year. Viruses’ phytoplankton massacres can also profoundly affect the world’s climate. Death and injury of some phytoplankton enhances production of dimethylsulfide, an oceanic gas that is the main natural source of sulfur in the air. A series of reactions transforms dimethylsulfide into airborne particulates that seed cloud formation and affect global storm cycles.

Even when they aren’t killing things, viruses are a force to be reckoned with. Viruses apparently manage much of the gene-trading between bacteria, for example. Such “horizontal gene transfer” is a recognized mechanism for passing antibiotic-resistance genes among bacterial species. And there’s increasing evidence that viruses may broker such exchanges across the kingdoms of life, as may be the case with the solar-powered sea slug.

The emerald-green sea slug Elysia chlorotica gets its hue and photosynthesizing skills from grazing on the algae Vaucheria litorea. Upon digestion, the algae’s light-harvesting factories—the chloroplasts—are sequestered in specialized cells in the slug’s gut (there’s even a name for this chloroplast theft: kleptoplasty). Photosynthesis continues, providing enough energy to sustain a slug for months without eating. Yet the chloroplast genome doesn’t contain all the necessary genes to make the light-harvesting factories run; genes from the algae’s nucleus are also required.

Puzzled about how the slugs maintain their solar power, scientists searched their nuclear DNA and found an algal photosynthesis gene, the team reported in 2008 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. That find adds to evidence of three other algae genes in the slug’s DNA. It appears that slugs today are born with algae genes that support photosynthesis, but still need to scarf some chloroplasts.

Intriguingly, scientists have also detected viruslike particles in the stolen chloroplasts and in the nuclei of the slug. While direct evidence remains elusive, the slugs may have originally acquired those photosynthesis genes via a virus.

Gene wheeler-dealers

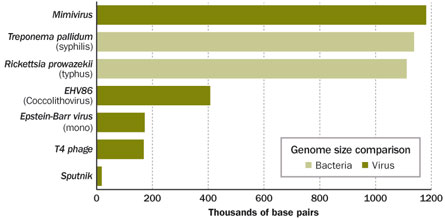

Viruses also may have introduced a DNA-repair gene into the octocorals, which include the organ-pipe coral and sea fans. Clues to this transaction come from relatives of one of the most spectacular viruses known today—the supersized beastie from the water tower in England. Now known as mimivirus, it’s more than 4,000 times the mass of the common cold virus. After its discovery, analyses of DNA from ocean samples revealed an abundance of mimivirus relatives. That search also led to the discovery of a version of MutS, a DNA-repair gene known from bacteria but never before seen in viruses.

So far, mimivirus’s marine relatives all seem to have this version of MutS. An octocoral ancestor may have acquired the gene from a marine mimivirus, sometime after the octocoral lineage split from that of the true corals, Claverie and colleagues reported in July in the Journal of Invertebrate Pathology.

In addition to acting as gene brokers, viruses appear to keep some of what they’ve garnered for themselves. Seven genes, part of a set needed for photosynthesis, were recently found in the genomes of viruses that infect marine cyanobacteria. These genes encode directions for making photosystem I, a protein complex that nabs electrons from proteins upstream in the photosynthesis chain. In a cyanobacterium, these genes are separated by good-sized chunks of DNA. But in viruses, the genes appear to have been packaged into a cassette, with two of the bacterial genes fused into one, scientists from the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology and other institutions reported online August 26 in Nature.

Because the genes are separated in the cyanobacterium but next to each other in the viral DNA, they probably represent multiple acquisitions, says Matthew Sullivan of the University of Arizona in Tucson. And the viral version of photosystem I might be able to nab more electrons than the algae version, and thus photosynthesize more efficiently.

“The virus definitely seems to have its own agenda,” says Shannon Williamson, director of environmental virology at the J. Craig Venter Institute in San Diego. Examples of coordinated gene collection by viruses are increasing, she notes. “It’s much more common than we anticipated, and we’re starting to see there really is no restriction on the types of genes they can acquire.”

As sampling of the oceans continues, similar instances of gene wheeling and dealing will probably emerge. The hunt for the viral photosystem I genes began with the scientists combing the database of DNA collected in the Global Ocean Sampling Expedition, which has so far done extensive collecting in waters from French Polynesia to Antarctica. The 2009–2010 expedition, now underway, includes visits to the Mediterranean and Black seas. Since these bodies of water are relatively isolated, they may harbor especially odd viruses.

Sullivan is part of a second virus-seeking mission, dubbed project OViD (ocean virus diversity), which began a three-year seafaring trip on September 4 to study the planet’s ocean ecosystems.

Scientists are pretty jazzed about these explorations of ocean microbial diversity. Yet viruses may be even more prevalent in soils than in the sea, Williamson says. She is working on a project to compare the diversity of viruses in agricultural and nonfarmed land. “Pretty much anywhere you look you are going to find viruses,” she says.

That includes freshwater locales, such as the water tower where mimivirus was discovered in 1992. It took a decade for scientists to realize that “Bradford coccus” wasn’t a bacterium, says Didier Raoult of CNRS in Marseille. Raoult had no luck trying to digest the critter’s cell wall and decided to image the thing with a scanning electron microscope. To his surprise, the “bacterium” looked like an iridovirus—icosahedral

viruses that infect some insects, fish and frogs. But it was enormous.

Viruses aren’t supposed to be visible under a light microscope; they are typically far too small. But mimivirus (“mimi” for mimicking microbe) isn’t just big for a virus, it’s bigger than some bacteria. Analyses of its DNA, cataloged in 2004, revealed that it also has more genetic material than some bacteria and certainly more than any other previously seen virus. The mimivirus genome contains genes for more than 900 proteins. (In contrast, T4—which, pre-mimi, was considered a large virus—has about 77 genes.) Some of the mimivirus genes appear to be involved in processes thought to be conducted only by cellular creatures—the virus’s hosts—such as translating messenger RNA into proteins. All in all, mimivirus seriously unsettled the world of virus research.

“I think the discovery really messed up the heads of a lot of people,” says Eugene Koonin of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md.

Mimvirus has proved startling on another front: It’s big enough that other viruses infect it. In September 2008 in Nature, scientists including Raoult and Koonin reported a new strain of mimivirus. Dubbed mamavirus, it is slightly larger than mimi and was also isolated from an amoeba. The mamavirus was infected with a smaller virus that the scientists called Sputnik. There was some speculation that Sputnik might just be coinfecting the amoeba, but a new analysis by Claverie and Chantal Abergel, to appear in the Annual Review of Genetics, reports that Sputnik is truly infecting mamavirus and cares little about the larger amoeba universe.

Putting viruses in their place

Discoveries of such bacteria-dwarfing viruses have revived an old debate about what it means to be alive and where viruses fit in the big evolutionary picture. More than 80 percent of mimi’s genes have no resemblance to cellular genes, suggesting that it isn’t an errant gene thief gone wild. This is true of much of the viral genetic material out there, Suttle says. “It’s like discovering unknown life-forms.”

No one gene is found in all viruses, but a small pool of genes, dubbed “hallmark genes” by Koonin, are found in many viruses. Because viruses infect all kinds of life and can be made of all forms of genetic material (DNA or RNA, either single- or double-stranded), Koonin argues that viruses may have predated cellular life. A sort of “previrus being” perhaps formed in the nooks of a hydrothermal vent, he speculates. Some scientists have even argued that viruses were involved in the origin of the nucleus. A fundamental split in the tree of life divides organisms with a nucleus—their DNA is sequestered from the cell’s cytoplasm in a protective membrane—from organisms without a nucleus. Eukaryotes, which include yeast, plants and people, have nuclei. Creatures without nuclei comprise a messy mixture of microorganisms, such as bacteria—and viruses, if they are included in the tree of life at all.

“Fundamentally, what is a nucleus?” asks Claverie. “Its goal in the cell is to replicate its own DNA using machinery outside of itself, in the cytoplasm. That’s what a virus does.”

Data don’t really support the nucleus-as-virus notion, says evolutionary biologist Anthony Poole of Stockholm University in Sweden. Studies suggest that the nucleus emerged from a cell folding into itself. But Poole still finds the virus idea interesting.

“Speculation in this field is quite important,” he says. “It can be nonsense, but it can lead to new ideas you can test and then we can progress a little bit.”

The role of viruses in the history of life—and whether viruses should be considered alive—was debated in a flurry of correspondence in the August Nature Reviews Microbiology. (Scientists including Koonin, Claverie and Raoult weighed in.) While the philosophical “life” question will probably remain unanswered, Raoult says, research clearly shows that viruses are a vital force, no matter how they are labeled. “Words are just to communicate,” he says. “They don’t reveal the truth.”