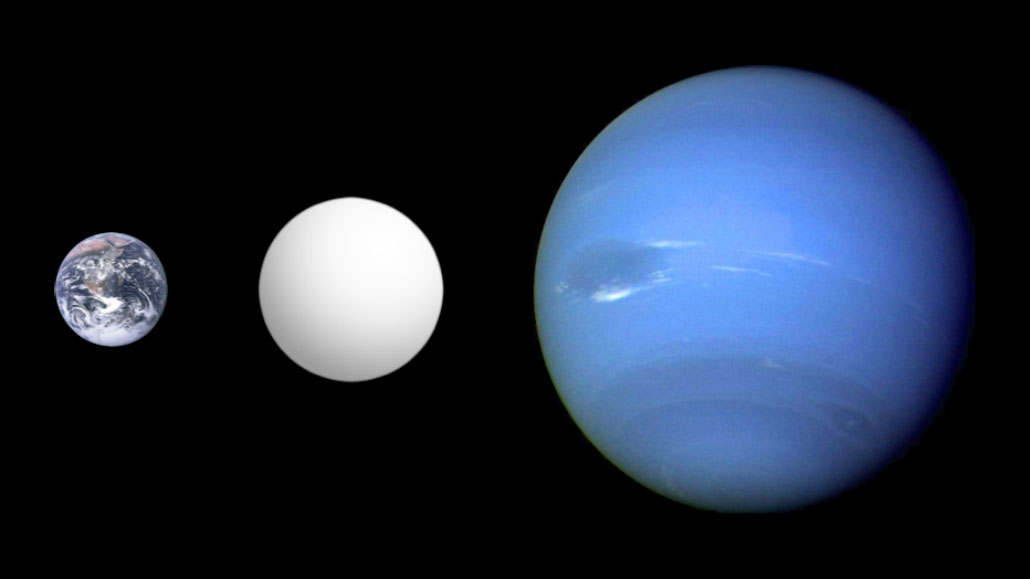

Some exoplanets may be covered in weird water that’s between liquid and gas

Wet, superheated worlds could bridge the divide between rocky and gaseous planets

Exoplanets between the size of Earth (left) and Neptune (right) are typically thought to be either rocky super-Earths or gaseous mini-Neptunes. Now, simulations suggest some of these planets (illustrated, center) could be rocky planets enveloped in water that’s not quite liquid and not quite gas.

Aldaron/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA 3.0)