‘Fen, Bog & Swamp’ reminds readers why peatlands matter

Novelist Annie Proulx chronicles people’s long history with wetlands and their ecological value

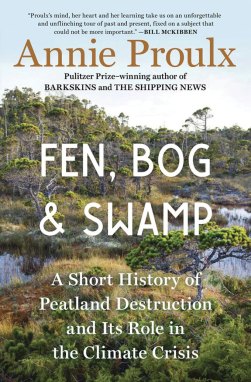

Trees and shrubs distinguish swamps, like this one in Louisiana, from other types of peatlands.

KAREN FOX/IMAGE SOURCE/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Fen, Bog & Swamp

Annie Proulx

Simon & Schuster, $26.99

A recent TV ad features three guys lost in the woods, debating whether they should’ve taken a turn at a pond, which one guy argues is a marsh. “Let’s not pretend you know what a marsh is,” the other snaps. “Could be a bog,” offers the third.

It’s an exchange that probably wouldn’t surprise novelist Annie Proulx. While the various types of peatlands — wetlands rich in partially decayed material called peat — do blend together, I can’t help but think, after reading her latest book, that a historical distaste and underappreciation of wetlands in Western society has led to the average person’s confusion over basic peatland vocabulary.

In Fen, Bog & Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and Its Role in the Climate Crisis, Proulx seeks to fill the gaps. She details three types of peatland: fens, which are fed by streams and rivers; bogs, fed by rainwater; and swamps, distinguishable by their trees and shrubs. While all three ecosystems are found around most of the world, Proulx focuses primarily on northwestern Europe and North America, where the last few centuries of modern agriculture led to a huge demand for dry land. Wet, muddy and smelly, wetlands were a nightmare for farmers and would-be developers. Since the 1600s, U.S. settlers have drained more than half of the country’s wetlands; just 1 percent of British fens remains today.

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

Only recently have the consequences of these losses become clear. “We are now in the embarrassing position of having to relearn the importance of these strange places,” Proulx writes. For one, peatlands have great ecological value, supporting a variety of wildlife. They also sequester huge amounts of carbon dioxide, and some peatlands prevent shoreline erosion, while buffering land from storm surges (SN: 3/17/18, p. 20). But the book doesn’t spend too much time on nitty-gritty ecology. Instead, Proulx investigates these environments in the context of their relationship with people.

Known for her fiction, Proulx, who penned The Shipping News and “Brokeback Mountain,” draws on historical accounts, literature and archaeological digs to imagine places lost to time. She challenges the notion that wetlands are purely unpleasant or disturbing — think Shrek’s swamp, where only an ogre would want to live, or the Swamps of Sadness in The Neverending Story that swallow up Atreyu’s horse.

Proulx jumps back as far as 20,000 years ago to the bottom of the North Sea, which at the time was a hilly swath called Doggerland. When sea levels rose in the seventh century B.C., people there learned to thrive on the region’s developing fens, hunting for fish and eels. In Ireland, “bog bodies” — many thought to be human sacrifices — have been preserved in the peat for thousands of years; Proulx imagines torchlit ceremonies where people were offered to the mud, a connection to the natural world that is hard for many people to comprehend today. These spaces were integrated into the local cultures, from Renaissance paintings of wetlands to British lingo such as didder (the way a bog quivers when stepped on). Proulx also reflects on her own childhood memories — wandering through wetlands in Connecticut, a swamp in Vermont — and describes how she, like writer Henry David Thoreau, finds beauty in these places. “It is … possible to love a swamp,” she says.

Fens, bogs and swamps are technically distinct, but they’re also fluid; one wetland may transition into another depending on its water source. This same fluidity is reflected in the book, where Proulx flits from one wetland to another, from one part of the world to another, from one millennium to another. At times didactic and meandering, Proulx will veer off to discuss humankind’s destructive tendency not just in wetlands, but nature in general, broadly rehashing aspects of the climate crisis that most readers interested in the environment are probably already familiar with. I was most enthralled — and heartbroken — by the stories I had never heard before: of “Yde Girl,” a redheaded teenager sacrificed to a bog; the zombie fires in Arctic peatlands that burn underground; and the ivory-billed woodpecker, a bird missing from southern U.S. swamps for almost a century.

Buy Fen, Bog & Swamp from Bookshop.org. Science News is a Bookshop.org affiliate and will earn a commission on purchases made from links in this article.