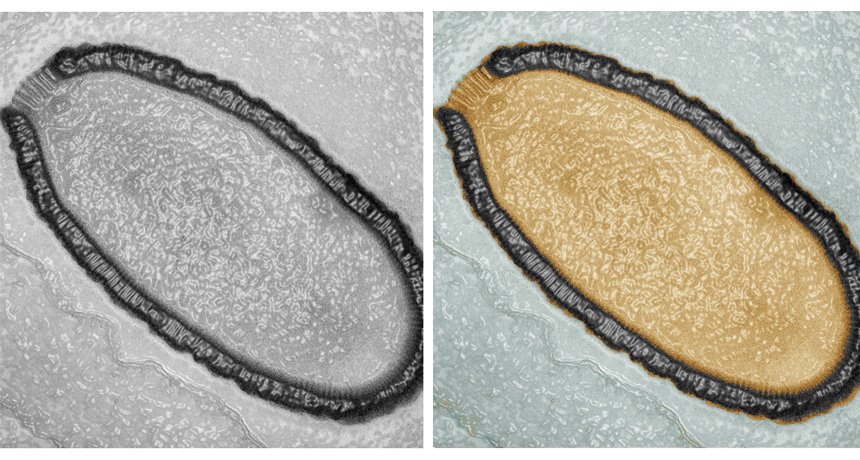

ENORMOUS MICROBE The largest virus ever discovered, Pithovirus sibericum, has been resurrected from 30,000-year-old- permafrost. In this electron microscope image and false-colored micrograph, the 1.5-micrometer-long virus rests in an amoeba cell.

JuliaBartoli and Chantal Abergel, IGS and CNRS-AMU