Aerial surveys in late March of the Great Barrier Reef have revealed “by far” the most widespread bleaching event to be recorded on the reef, researchers say.

ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is currently experiencing its third mass bleaching in just five years — and it is the most widespread bleaching event ever recorded.

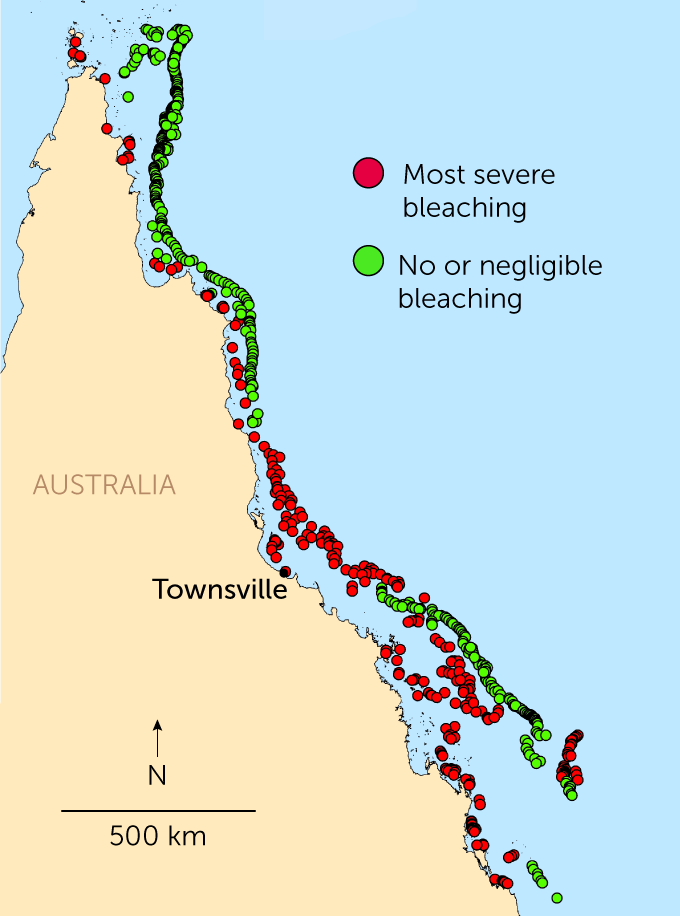

Results from aerial surveys conducted along the 2,000-kilometer-long reef over nine days in late March, and released April 7, show that 25 percent of 1,036 individuals reefs surveyed were severely affected, with more than 60 percent of corals bleached. Another 35 percent of the reefs had less extensive bleaching.

“This is the second most severe event we have seen, but it is by far the most widespread,” says marine biologist Terry Hughes, director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University in Townsville, Australia, who led the aerial surveys along with scientists from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

What is most concerning this year is that the southern third of the reef, which escaped unscathed in 2016 and 2017, is now extensively bleached, too. “For the first time we have seen bleaching in all three regions of the reef — the north, the middle and the south,” Hughes says.

Bleaching occurs when corals experience periods of unusually high summer sea temperatures, and they eject the symbiotic algae that both nourish corals and give them some of their colors (SN: 10/18/16). It’s not a guaranteed death sentence, but many corals will not survive.

The first mass bleaching recorded on the Great Barrier Reef was in 1998, with the next in 2002. But bleaching events in 2016, 2017 and now 2020 have scientists seriously concerned, as there has been little time for reefs to recover in between episodes (SN: 11/29/16; SN: 4/11/17).

“We are seeing more and more bleaching events and the gap between them is shrinking,” Hughes says. “Those gaps are important because that’s the opportunity for corals to rebound and make a recovery…. It takes about a decade for the fastest-growing corals to fully rebound.”

Too hot spots

Aerial surveys along the 2,000-kilometer-long Great Barrier Reef over nine days in late March revealed more widespread bleaching than ever before recorded. While the reef suffered bad bleaching events in 2016 and 2017, most of the impact then was north of Townsville. In 2020, damage was recorded from the tip of the continent to well south of Townsville.

Where bleaching was observed on the Great Barrier Reef in 2020

While scientists saw reefs in the northern and central regions of the Great Barrier Reef begin to recover following 2016 and 2017, they now have concerns that progress has been for nothing.

“They are just getting hammered by these repetitive, destructive heat waves,” says Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, who studies coral reefs at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia. “If this continues over the next 10 years or so, there won’t be much of a Great Barrier Reef left.”

Hoegh-Guldberg — who is also the deputy director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, but was not involved in the survey work — says while the extent of the bleaching is an “absolute tragedy, it’s one we’ve been expecting.” February 2020 had the warmest sea surface temperatures on the Great Barrier Reef since records began in 1900, according to figures released in March by Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology.

Hoegh-Guldberg argues that, aside from governments taking action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, one thing that can be done is to map out those individual reefs that are less exposed to the effects of climate change than others, such as areas protected by upwellings of cooler water (SN: 9/25/19). These sites may be the source of coral larvae to regenerate bleached reefs in the future, and should be especially protected from other damage, such as from agricultural runoff, he says.

“That’s one place I think we can do further work,” Hoegh-Guldberg says. “Identify those areas that are least exposed to climate change and which have the greatest role to play in any renewal.”

But Hughes notes that “the problem with that approach is that we are running out of reefs that haven’t yet bleached.” He led a study published in Nature in 2019 showing an 89 percent decrease in numbers of coral larvae released in 2018 from reefs that had been damaged in 2016 and 2017. “The ability of the reef to rebound has been compromised,” he says.

“We are in uncharted territory in terms of rebound potential. We are not sure what the Great Barrier Reef will recover to anymore. The mix of species is changing and really quickly,” Hughes says. “Optimistically, if temperatures don’t rise too much more, we’ll still have a reef, but it’s going to look very different.”