Hairy cells in the nose called brush cells may be involved in causing allergies

In mice, these cells trigger inflammation when exposed to mold and dust

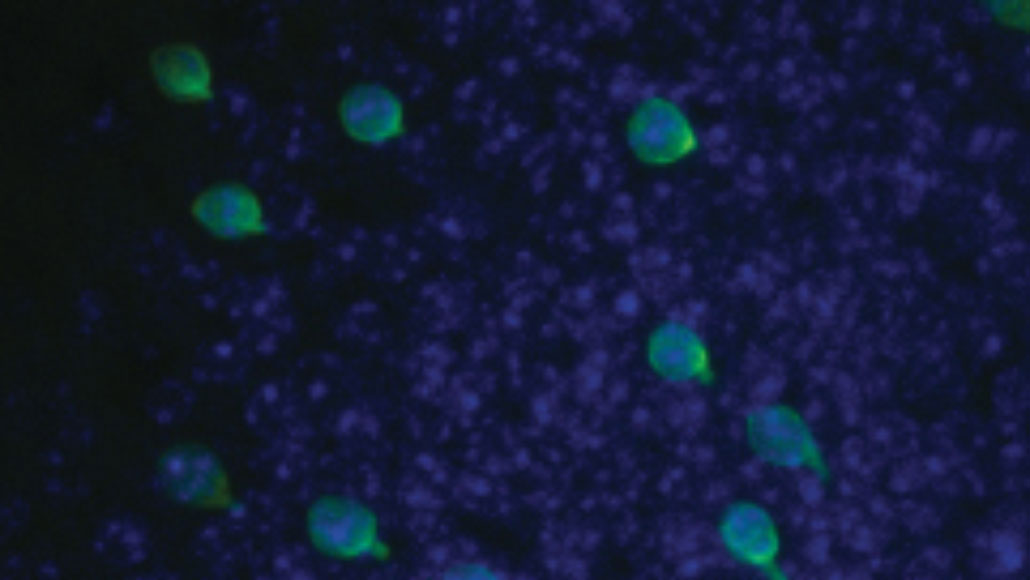

Brush cells (green) are abundant in the lining of a mouse’s olfactory bulb, which senses odors. The cells help detect invaders, including ones linked to allergies.

S. Ualiyeva et al/Science Immunology 2020