Hunting Hidden Dimensions

Black holes, giant and tiny, may reveal new realms of space

In many ways, black holes are science’s answer to science fiction. As strange as anything from a novelist’s imagination, black holes warp the fabric of spacetime and imprison light and matter in a gravitational death grip. Their bizarre properties make black holes ideal candidates for fictional villainy. But now black holes are up for a different role: heroes helping physicists assess the real-world existence of another science fiction favorite — hidden extra dimensions of space.

Astrophysical giants several times the mass of the sun and midget black holes smaller than a subatomic particle could provide glimpses of an extra-dimensional existence.

Out in space, astrophysicists are looking hard to see if large black holes are shrinking on a time scale that might be detected by modern telescopes. If so, it might mean the black holes are evaporating into extra dimensions.

In the laboratory, black holes far smaller than anything that could be seen with a microscope might be produced in Europe’s Large Hadron Collider after it starts running again in November (SN: 7/19/08, p. 16). The detection of such a black hole, which would evaporate in a hail of subatomic particles in a tiny fraction of a second, would provide evidence that unseen dimensions of space exist.

What makes either of these ideas even plausible is a bold theory put forth just over 10 years ago that purports to explain the weakness of gravity by supposing that some of it is leaking out into extra dimensions.

Gravity feels strong to humans because it makes climbing hills hard. But one of the fundamental paradoxes about gravity is demonstrated by the fact that an ordinary refrigerator magnet can pick up a paperclip — counteracting the entire mass of the Earth pulling down on the clip.

Physicists call this the “hierarchy problem,” referring to the fact that all the other forces of nature are more than 30 orders of magnitude stronger than gravity.

“It’s hard to explain such a huge number from any mathematical postulate or any physical principle,” says Greg Landsberg, a theoretical physicist at Brown University in Providence, R.I. “It’s a bit of an embarrassment for our field, because what it really means is, we don’t seem to understand gravity.”

Measuring extra dimensions

Isaac Newton declared in the 17th century that gravity gets weaker by the square of the distance between two objects. If the moon were twice as far from Earth, it would feel one-quarter the gravity.

But in 1998, theoretical physicists Nima Arkani-Hamed, Savas Dimopoulos and Gia Dvali pointed out that gravity had never been measured below a distance of about a millimeter. Suppose, they suggested, that gravity differs from Newtonian expectations at distances smaller than a millimeter.

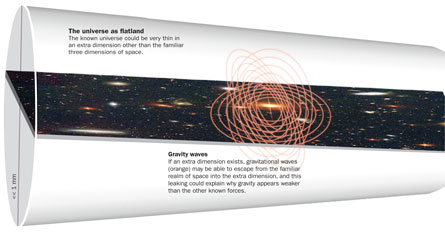

That could happen if there are extra dimensions of space that gravity leaks into. These hidden dimensions might be shaped, for example, like the circumference of a hose. From a distance, the hose looks like a one-dimensional line, but seen up close, it has a curled-up second dimension. Arkani-Hamed, Dimopoulos

and Dvali — whose model is known as ADD, short for their names — suggest that there could be extra dimensions as large as a millimeter in diameter.

“In principle, the extra dimensions can be so small, like trillions and trillions of times smaller than a millimeter, and that’s what string theory predicts,” says theoretical astrophysicist Dimitrios Psaltis of the University of Arizona in Tucson. But “if you introduce those large extra dimensions, then gravity can get diluted in some way.”

Gravity may spread into the extra dimensions while the other known forces and particles are confined to the three familiar spatial dimensions. So gravity could be just as strong as the other forces — but only felt strongly at short distances.

Tiny curled extra dimensions aren’t the only possibility. In 1999, theoretical physicists Lisa Randall and Raman Sundrum proposed that one extra dimension might stretch out to infinity. If either theory is true, it would also mean that at very small distances, gravity would be much stronger than Newton’s prediction.

The idea of “large” extra dimensions sent experimental physicists scrambling.

So far, physicists using sensitive small-scale experiments have measured the force of gravity at distances just under 50 micrometers and haven’t found any deviation from Newton’s law yet. But they keep looking.

Shrinking black holes

Black holes, as the most gravitationally dense objects in the universe, might provide another way of testing the extra-dimension hypotheses. Black holes know a thing or two about gravity; the trick is getting them to reveal their secrets.

In the 1970s, theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking calculated that black holes actually lose mass. That mass vanishes over time in the form of what’s now called Hawking radiation. “Over time” generally means over billions of years, like the age of the universe. The larger the black hole is, the more slowly it shrinks. But as it gets smaller, the evaporation rate accelerates.

And if there are extra dimensions of the Randall-Sundrum type, astrophysical black holes might emit gravity waves into these other dimensions and shrink faster than otherwise expected. So, Psaltis thought, finding a small black hole that’s really old would limit the size of the extra dimensions. “If you notice that a black hole lived, for example, a hundred million years,” Psaltis says, “that means that it couldn’t have evaporated, couldn’t have lost its mass really, really fast.”

But finding out the age and weight of a black hole is about as tricky as discovering that of a vain movie star. So Psaltis tried to find a way to get the black hole to reveal a little bit more about itself.

He found a black hole that looked like it had been kicked out of the plane of the Milky Way galaxy following a violent supernova explosion, like a fastball hit over the wall at Fenway Park. Since the black hole would have been born in the explosion, Psaltis could estimate its age by measuring how fast it and its companion star were zooming away from the galaxy, then backtracking to find out how long ago it had been ejected.

He calculated that this particular black hole, J1118+480, was a minimum of 11 million years old. Using that age and an estimated mass, Psaltis put an upper limit of 80 micrometers on the size of any extra dimensions, as he reported in Physical Review Letters in 2007.

Tim Johanssen, Psaltis’ graduate student, came up with another idea for measuring whether black holes are losing weight, one that doesn’t depend on knowing their ages. Most black holes a few times the mass of the sun have been detected because they orbit a companion star. The masses of the star and the black hole, as well as the distance between them, determine how fast the two rotate around each other, like Olympic pair skaters spinning around each other in a death spiral. If the mass of the black hole is changing, the rate at which it and its companion orbit each other, called the orbital period, changes as well.

Johanssen calculated how quickly a black hole would have to lose mass in order to see a noticeable difference in the orbital period. “Just from normal astrophysical mechanisms, we would expect [the period] to halve or double at a time-scale on the order of the age of the universe, billions of years,” says Psaltis. “If extra dimensions exist, and they are as large as, say, a tenth of a millimeter, then that time scale goes down to about several millions of years. Which means that if you make an observation over a year, you expect a change in the orbital period of a few parts per million. This is tiny, but this is something that modern observations of binary systems can actually do.”

Johanssen, Psaltis and astronomer Jeffrey McClintock of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics looked closely at the best-studied black hole binary, A0620-00, which has been observed for about a decade. So far, they found, there has been no observable change in its orbital period. That let them constrain the size of the extra dimension to less than 161 micrometers. Their results appeared in February 2009 in the Astrophysical Journal.

Another researcher, Oleg Gnedin of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, extrapolated from Psaltis’ work. Gnedin learned of a recently discovered black hole in a globular cluster, one of the oldest groups of stars in the universe. Black holes in globular clusters are on the order of 10 billion years old. The mere existence of a black hole this old puts a very tight constraint — less than 3 micrometers — on the size of the Randall-Sundrum extra dimensions, Psaltis says. That work was published online at arXiv.org in June (SN: 8/1/09, p. 7).

Although the globular cluster work sets the tightest constraint on extra-dimension size so far, the researchers admit that it relies on a lot of assumptions.

Psaltis is pinning his hopes on observations of binary systems because, he says, they’re “a measurement of what is happening right now to the black hole that we are seeing. It does not depend on the history.” He says that even though the researchers haven’t seen any changes in orbital periods so far doesn’t mean the extra dimensions don’t exist, just that they haven’t been found yet. Any change in orbital period, he says, would challenge physicists’ current theory of forces and particles in the universe — called the standard model.

But even if the extra-dimension theories are correct, observers still may never find evidence of such dimensions in the astrophysical black holes. One reason may be that the extra dimensions are of the ADD variety, small and curled up, in which case these tiny dimensions make no difference to the massive black holes in outer space.

The other reason may be that black holes don’t really evaporate faster into other dimensions even if they do exist, says Randall, the Harvard theoretical physicist who coauthored two of the popular extra-dimension models. “People have suggested that the decay rates of black holes might be a way of distinguishing” between the models, she says, “but it’s not fully resolved.”

Micro black holes

It will become pretty clear that large extra dimensions exist if a micro-sized black hole happens to appear in the Large Hadron Collider, or LHC, near Geneva. That’s because if gravity really is much stronger than expected at distances around a few micrometers or so, the LHC may be able to pack enough matter and energy into a small enough space that the system will automatically collapse into a black hole.

But before anyone starts worrying about Geneva disappearing into a black hole, know that this gravitationally dense midget wouldn’t even cross the diameter of an atomic nucleus before disintegrating (SN Online: 6/24/08).

“In this sense, these black holes are completely organic,” says Landsberg. “You could put them in your salad, and you wouldn’t notice that they exist because they immediately evaporate.”

But they might make their presence known to the LHC’s detectors.

That’s the province of a number of theoretical physicists, including Glenn Starkman of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Starkman led a team that developed a computer program, called BlackMax, that tells researchers what subatomic debris a black hole might leave behind as evidence.

Inside the LHC, two beams of protons will stream at speeds close to the speed of light in opposite directions around a circular tunnel. Protons are actually somewhat spread out, says Starkman,and mostly made up of subatomic particles called quarks and gluons. It’s extremely unlikely that any two of these particles will hit each other exactly head-on. But if two quarks or two gluons, or one of each, get close enough to each other as they are flying in opposite directions, there could be enough energy in a small enough space that a black hole would form — if, and only if, gravity is strong enough to start playing a role. “For that to happen,” says Starkman, “there have to be more than three dimensions.”

The black hole would evaporate almost instantaneously, perhaps in a hail of subatomic particles shooting forth in all directions, like a cherry bomb firecracker. Or perhaps researchers would see a signature event in which some of the energy disappears, carried away into other dimensions by gravitons — the invisible gravitational counterpart to the photon.

The good thing, from a theoretical physics point of view, is that if the LHC makes any black holes at all, it will make a lot of them — as many as one per second, or 30 million a year. “Now, 30 million a year may involve optimistic assumptions, but perhaps a million or a hundred thousand or even ten thousand is not impossible,” says Stanford University’s Savas Dimopoulos, the middle “D” of the ADD extra-dimension hypothesis. “Even if you have 10,000 black holes, that is a lot of events to do statistics with and to start testing in detail both the existence of the black hole and the framework of large dimensions.”

Randall, like many, is skeptical. “It’s a cute idea,” she says. But with coauthor Patrick Meade, then at Harvard and now at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., she argues that the scenario is highly unlikely. Their work was published in May 2008 in the Journal of High Energy Physics.

“It’s virtually impossible that you’re going to make genuine black holes at the LHC because the energy isn’t really high enough,” she says. “You could see some evidence of interesting gravitational effects in higher dimensions in terms of how things would scatter off each other … but it seems very unlikely that you would actually have anything that is really a genuine black hole.”

Still, there are a lot of uncertainties, and until the LHC is up and running, no one will really know.

Dimopoulos, for one, remains optimistic, but he has hedged his bets. In addition to large extra dimensions, he has a stake in two other leading candidates for solving the hierarchy problem. These theories, called technicolor and supersymmetry, don’t rely on extra dimensions — and they both might show their colors at the LHC.

But chances are “that nature may choose a completely different route, and it may be that the solutions to the hierarchy problem will be something that nobody ever thought about,” he says. “And that may be the most exciting scenario for what we will discover.”

Diana Steele is a freelance science writer based in Oberlin, Ohio.