In the heavyweight division, immune cells embedded in fat pack some extra disease-causing punches, a new study shows.

Those punches involve potentially dangerous proteins linked to inflammation, heart disease and diabetes. Something in the adipose tissue, or fat, of overweight people primes immune cells called macrophages nestled within the tissue to release the proteins when the cells sense high levels of fat in the bloodstream, researchers report in the Feb. 24 Science Translational Medicine. The discovery may lead to treatments that could block disease formation in overweight or obese people.

Blood levels of free fatty acids, such as triglycerides, rise after a high-fat meal and, in obese people, are often constantly elevated to levels two to three times higher than normal, says Preeti Kishore, an endocrinologist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City.

In the new study, Kishore and her colleagues show that these types of fat particles prod immune cells called macrophages to make PAI-1, a protein linked to heart disease. The protein, whose full name is plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, keeps blood clots, which can cause strokes or heart attacks, from breaking up.

The fatty acids also triggered the release of inflammation-causing proteins called TNF-alpha and IL-6, the researchers found. Inflammation caused by those and other proteins is thought to play a role in type 2 diabetes in obese people.

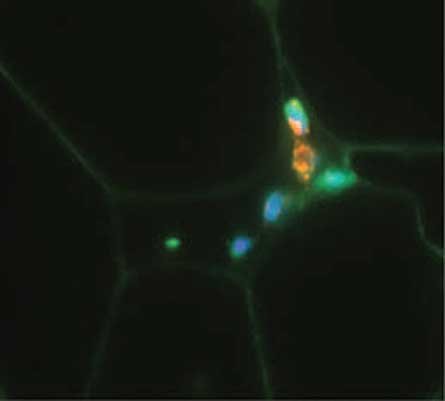

Scientists had already discovered that overweight and obese people have more macrophages in their fat tissue than do lean people. But, says Carey Lumeng, a pediatrician at the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor, “Nobody really knew — and we still don’t know — what exactly these macrophages are doing.”

The new study suggests that macrophages may tell fat tissue what is going on in the outside environment, which the macrophages sense through substances circulating in the blood, Lumeng says. And fat cells seem to communicate with macrophages, too, priming the immune cells to rapidly respond to dietary changes.

Kishore and her colleagues studied 30 overweight people, with an average body mass index of 28 (a BMI of 25 to 29.9 is overweight, and 30 or higher is considered obese) and an average age of 37. The researchers steadied the volunteers’ blood sugar levels, then injected an intravenous solution containing free fatty acids in concentrations that mimic the higher levels seen in obese people. The fat infusion is a standard formula used when feeding people intravenously. Within five hours, levels of PAI-1 and inflammatory proteins rose and impaired the volunteers’ sensitivity to insulin. Insulin insensitivity is a hallmark of type 2 diabetes.

The researchers took biopsies of stomach fat from the volunteers and found that macrophages, rather than fat cells, made the disease-linked proteins.

In further experiments with macrophages grown in the laboratory, Kishore and her colleagues discovered that free fatty acids alone didn’t prod macrophages to release PAI-1 or inflammatory chemicals. The cells also needed an as-yet-unidentified signal from fat cells before the macrophages would manufacture the proteins.

“Inflammation is a normal, healthy process, but under certain conditions it becomes inappropriately activated,” Kishore says. As people pack on pounds, their macrophages become more sensitive to dietary signals. “When these macrophages are activated,” she says, “they make more of these proteins that are bad for you.”