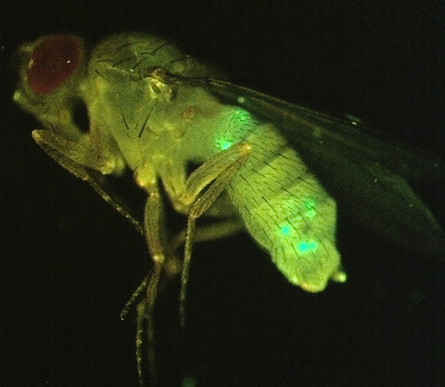

GREAT EXPECTATIONS Fruit flies have their own versions of anticipating events, and failure to mate or eat as expected turns out to have physiological costs.

DChai21/Wikimedia Commons

Smelling female fruit flies but not mating with them can actually shorten males’ lives.

Drosophila melanogaster males not allowed to mate despite receiving tantalizing chemical sex messages lose about 35 to 40 percent of their normal life span, says molecular geneticist Scott Pletcher of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Males’ fat stores also dwindle, and the flies prove less able to cope with starvation, Pletcher and his colleagues report November 28 in Science.

Creating the reciprocal situation of celibate females sniffing but not getting males wasn’t as easy, he says. But so far, experiments show female life span declining 15 to 20 percent too.

This marks the second time Pletcher and his colleagues have linked premature demise with frustrated expectations. Fruit flies on a low-calorie diet, which normally would lengthen lives and sustain health, lost some of the diet’s benefits if they lived with the smell of food they couldn’t eat, he and colleagues reported in 2007.

Like a person salivating at the odor of a pie baking, flies pick up cues to likely events and start to prepare physically. Their brains may be monitoring the expected events as well as what the flies actually experience, Pletcher speculates, and “bad things happen when they don’t match up.”

Males escaped much of the damage of the frustrating experience if they could mate with females afterward, the researchers found.

Rescuing the expectation-denied males, however, required an unusually high 5-to-1 female-to-male ratio, notes Jennifer Perry of the University of Oxford. She points out that in Pletcher’s experiments, routine 1-to-1 mating opportunities didn’t much affect the premature demise of frustrated males.

The males, however, had been set up to have unusually high expectations: The researchers had surrounded five males with 25 female-scented brethren.

The detectors for those sex-signaling compounds were particular molecules in male fruit flies’ forelegs, Pletcher and his colleagues determined. Fruit flies have abundant ways of sniffing and tasting their environment. When Pletcher and his team sabotaged a molecular sensor in the legs, scent-exposed flies had normal life spans.

The experiments may help explain why male animals of many species have shorter lifespans than females, says Urban Friberg of Uppsala University in Sweden. Males often face “harsh” competition for mates, he says, and he thinks unfulfilled expectations may turn out to be less of a problem for females.

A nugget of support for the idea that many animals could experience frustration effects, Pletcher says, comes from a paper on longevity in nematodes also appearing in Science. Hermaphrodite nematodes that wriggle around on lab dishes where males once congregated have shortened life spans, reports Anne Brunet of Stanford University and her colleagues. There’s no mating between the males and the hermaphrodites — again, the mere perception of secretions from a different sex triggers physiological consequences.