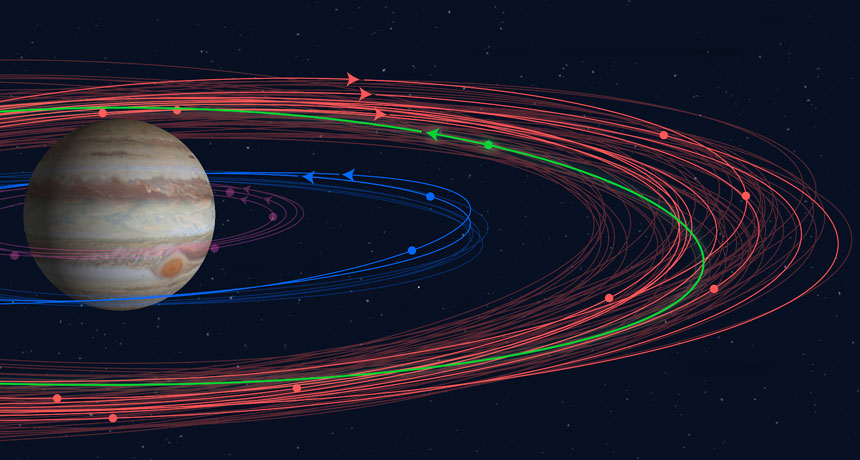

Jupiter has 12 more moons than we knew about — and one is bizarre

An oddball satellite, called Valetudo, may collide with its neighbors within a billion years

NEW MOON, I SAW YOU ORBIT ALONE Of 12 recently discovered Jovian moons (illustrated in bold orange, blue and green), one orbits in the opposite direction of its neighbors (arrows show orbit direction). Four moons discovered by Galileo are also shown (purple).

Roberto Molar Candanosa/Carnegie Institution for Science