FLOATING ISLANDS Sargassum seaweed (shown off of Florida’s Big Pine Key) can form vast mats in the ocean that shelter everything from turtles to eels to fish. But blooms of the algae are becoming more extensive, posing a problem for coastlines.

Brian Lapointe/Florida Atlantic University's Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute

During the summer, vast, floating islands of Sargassum algae can blanket entire parts of the tropical Atlantic Ocean. The algae reached their largest extent on record in June 2018, forming a giant brown belt that extended for 8,850 kilometers from the west coast of Africa into the Gulf of Mexico. At least 20 million metric tons of Sargassum made up the belt, the largest bloom of seaweed ever detected, researchers say.

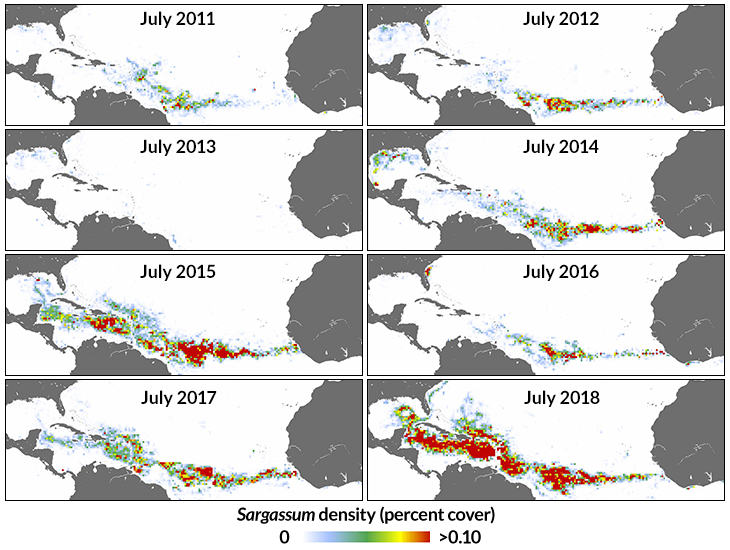

Satellite data tracking the extent of the mats over the last 19 years reveal a sudden, dramatic increase in the summer of 2011, and recurring almost every year since, the scientists report in the July 5 Science.

These annual massive mats of seaweed, which the researchers have dubbed the great Atlantic Sargassum belt, have been fueled in part by increasing nutrients pouring into the ocean from the Amazon River, the study suggests. Forests can both filter and regulate the flow of water from land to ocean. But with increasing fertilizer use and deforestation anticipated in the coming decades along the Amazon’s tributaries, such colossal blooms may become a new normal.

The floating algae islands have long provided an important shelter for turtles, fish, crabs, eels and other marine species (SN Online: 4/13/17). But there can be too much of a good thing, particularly when Sargassum mats crowd coastlines. They can smother corals and seagrass, and wreak havoc on coasts across the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico as heavy, meters-thick layers of the seaweed wash up on beaches and rot (SN Online: 8/28/15).

To track the waxing and waning of the Sargassum, the researchers, led by optical oceanographer Mengqiu Wang of the University of South Florida in Tampa, used data from satellite instruments that scan the ocean in visible and infrared light wavelengths. Sargassum algae, like photosynthesizing plants, contain abundant chlorophyll-a. That pigment pings brightly at infrared wavelengths, creating a sharp and easily detectable contrast to the darker water beneath.

From 2000 to 2010, there was little of the algae in the central Atlantic, with the occasional patch near the mouth of the Amazon River in the summer and fall. But a tipping point occurred in 2011, when the line of seaweed suddenly and dramatically extended all the way across the ocean, the team found.

That change in 2011 “was really surprising,” says James Gower, an optical oceanographer at Fisheries and Oceans Canada in North Saanich, British Columbia, who coauthored a commentary in the same issue of Science. “It really stood out in the satellite data.”

Each year since, except 2013, the algae have formed a similar, vast belt. In 2018, that belt was the largest and densest yet, the team reports, containing at least 20 million metric tons of algae — about four times the weight of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Bloom belt

Since 2011, satellites have detected a wide swath of Sargassum algae, dubbed the great Atlantic Sargassum belt, extending from the west coast of Africa to the Gulf of Mexico each July (monthly mean density, shown). The year 2013 is the one exception, when above-average sea-surface temperatures may have suppressed the seaweed’s growth. The largest extent on record occurred in 2018.

Sargassum algae growth in the Atlantic Ocean in July, 2011–2018

Two sources of nutrients appear to be feeding the blooms: discharge from the Amazon River and upwelling along the coast of West Africa. Upwelling, in which surface waters are pushed aside by strong prevailing winds, allowing deeper, nutrient-rich waters to rise toward the surface, occurs there naturally, due to the interaction of winds, ocean and the rotation of the Earth.

How those nutrients will change in the future is uncertain. There’s a lot that scientists still don’t know about the sources of those nutrients, as well as how climate change will affect the seaweed’s life cycle. Nutrients carried on dust blown into the ocean from the Sahara, as well as inputs from Africa’s Congo River, may also have a role. And, particularly warm sea-surface temperatures, such as occurred in 2013, appear to suppress the algae’s growth, the team notes. That casts some doubt on the fate of the blooms in a warming world.

Having this global eye on the seaweed has been key to beginning to understand the sudden growth. Even higher-resolution satellite data collected over the world’s oceans could help researchers better track the movement of the algae and suss out what’s really causing the blooms, Gower says.