From the May 23, 1936, issue

SEAWORTHINESS OF NEW SHIP INSURED BY SOUND PLANNING

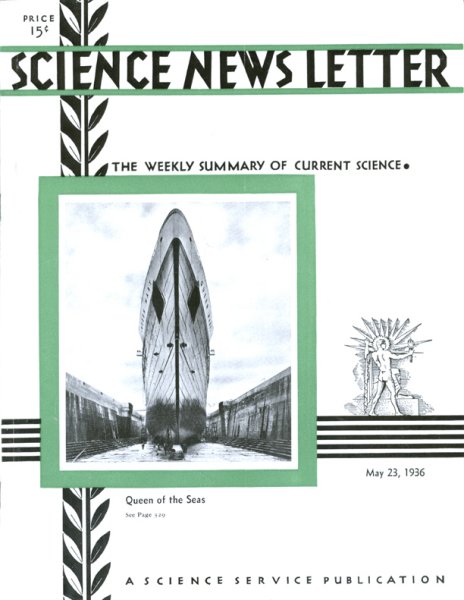

Ships designed to cross the North Atlantic in winter as well as summer must stand such enormous stresses as are engendered by high seas. Into the Cunard White Star liner Queen Mary, destined for year-round service, experienced builders instilled seaworthiness by means of sound planning.

Structure as required by the British Board of Trade was the first consideration, and no concessions were asked for by designers of the ship’s interior. Beauty within the ship consists of arranged construction, embellished with an economic, sparing, and studied use of ornament. For good and practical reason, the Queen Mary does without the glories of unbroken vistas extending the length of the upper deck.

Her three direct uptake funnels arranged along the center line of the ship continue directly upward to their outlets, instead of being deflected up the sides and over the promenade deck, as is the case with a number of vessels of Continental design. In addition, two large engine hatchways are installed further aft along the centerline. Taken together, the funnels and hatchways comprise five unbroken elements of structural steel rigidity extending through the entire height of the ship, into which extraheavy deck plates and girders were tightly woven, the whole bracing the horizontal structure at every level.

Extrathick plating was provided for the ship’s double hull, which extends as far up as the waterline, and for her sides and decks, while ribs are more closely spaced than heretofore. The great strength built into the hull is borne out by the vessel’s weight, her 77,500 tons displacement exceeding that of any other ship by about 10,000 tons. And the Queen Mary has a longer waterline length—1,004 feet—than that of any other ship, yet she is several feet shorter than the longest overall. This can only mean that the Queen Mary has the greatest foundation or supporting size with relatively less superstructure to carry. Other things being equal, it is the primary factor of waterline length that determines added steadiness and speed.