Mental puzzles underlie music’s delight

Brain activity reflects how much people enjoy a particular new tune

Whether you’re rocking out to Britney Spears or soaking up Beethoven’s classics, you may be enjoying music because it stimulates a guessing game in your brain.

This mental puzzling explains why humans like music, a new study suggests. By looking at activity in just one part of the brain, researchers could predict roughly how much volunteers dug a new song.

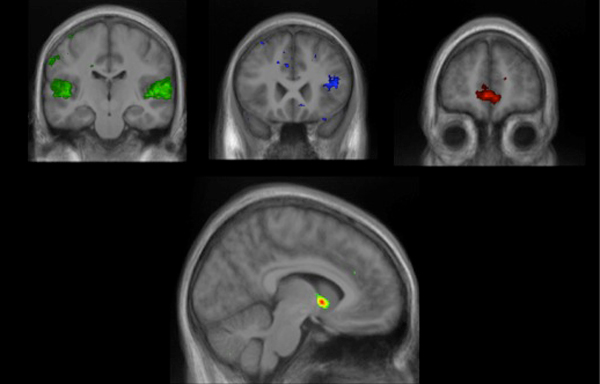

When people hear a new tune they like, a clump of neurons deep within their brains bursts into excited activity, researchers report April 12 in Science. The blueberry-sized cluster of cells, called the nucleus accumbens, helps make predictions and sits smack-dab in the “reward center” of the brain — the part that floods with feel-good chemicals when people eat chocolate or have sex.

The berry-sized bit acts with three other regions in the brain to judge new jams, MRI scans showed. One region looks for patterns, another compares new songs to sounds heard before, and the third checks for emotional ties.

As our ears pick up the first strains of a new song, our brains hustle to make sense of the music and figure out what’s coming next, explains coauthor Valorie Salimpoor, who is now at the Baycrest Rotman Research Institute in Toronto. And when the brain’s predictions are right (or pleasantly surprising), people get a little jolt of pleasure.

All four brain regions work overtime when people listen to new songs they like, report the researchers, including Robert Zatorre of the Montreal Neurological Institute at McGill University

The links between the brain’s reward center and the three other areas explain how simple sounds strung together in complex patterns can give humans so much joy, Salimpoor says. Music theorists have speculated that new music might tickle people’s pleasure centers by engaging their minds in play. But until now, no one had matched up the theory to the neurobiology.

In the study, the researchers examined the brain activity of 19 people as they listened to short clips of new music in an MRI machine. At the end of each clip, volunteers could choose to buy songs they liked, using their own money. The researchers asked them how much they would be willing to pay, $0.99, $1.29 or $2, in a system similar to iTunes. If volunteers did not like a song, they could choose not to buy it.

Then researchers compared brain scans of participants who bid different amounts on songs. Amid the bustle of activity in the brain, the nucleus accumbens leapt to life when people heard songs they wanted to purchase. The more money people chose to spend, the livelier their nucleus accumbens was while listening.

Teaming neuroimaging with the iTunes-like system for buying music was “a very clever idea,” says cognitive neuroscientist Aniruddh Patel of Tufts University in Medford, Mass. “It’s a nice application of new technology to address an old theory in music cognition,” he says. And in fact, the new findings seem to fit well with the old theory, he says.

The results tap into the fundamental ways our brains deal with sound, says auditory neuroscientist Nina Kraus of Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. “The implications are rather enormous,” she says. The work could help scientists better understand how humans decipher other complex sounds, such as speech.