Mosquitos use it to suck blood. Researchers used it to 3-D print

Using parts freely found in nature could help democratize 3-D printing, researchers say

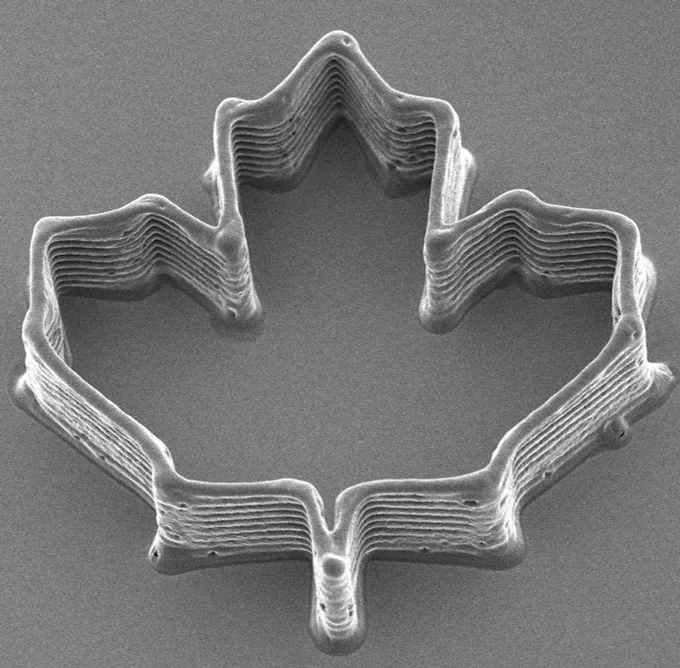

The proboscis of a mosquito (seen in a scanning electron microscope image of one insect’s head) is used for piercing skin. It’s also perfect for precision 3-D printing.

DENNIS KUNKEL MICROSCOPY/Science Source