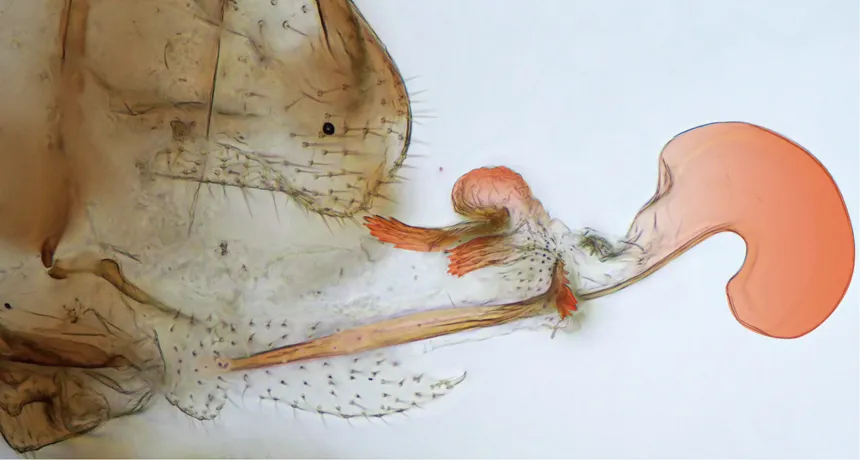

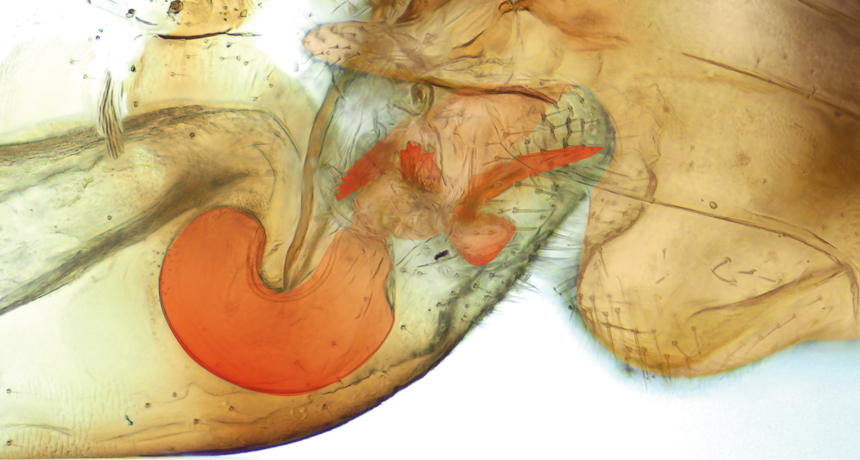

HERS, NOT HIS A small female Neotrogla bark louse extends an inflatable, penislike organ (less than a millimeter long, shown in orange), which fits into a vaginalike pocket inside the male of her species and collects his sperm.

Courtesy of K. Yoshizawa

The most dramatic genital-shape reversal known — females with long, insertable organs and males with corresponding pouches — has turned up in bark lice living in Brazilian caves.

A female in each of the four Neotrogla species extends a skinny structure up to 15 percent the length of her body to retrieve sperm from the male’s body, reports entomologist Kazunori Yoshizawa of Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan. Depending on the species, a female bark louse can spend up to 70 hours extracting sperm. Males have penislike remnants but can’t deliver sperm with them.

Male sperm packages look as if they could be nutritional bonanzas in dry caves where the insects otherwise rely on bat guano and the occasional carcass, Yoshizawa says. The food value of sperm may change the balance of various evolutionary pressures and end up favoring the evolution of female penises and male vaginas, the researchers suggest in the May 5 Current Biology.

“Absolutely amazing,” Menno Schilthuizen of Leiden University in the Netherlands emailed after a first look at the paper’s anatomical illustrations. The female organ, he says, “has even copied the penis spines that are so common in many male animals.”

Spines may help a female louse anchor her organ inside the male, Yoshizawa says. In three species, males have pouches, and bulges accommodate the spines and may reduce their damage to the males. When the female inserts the structure, it inflates and remains firmly attached. Once, when researchers tried to separate a coupled pair, the male’s body broke in two but male and female genitals remained connected.

The gripping power is just one of the features that distinguish the cave lice penis from the few other known examples of insertable female organs, Yoshizawa says. A female seahorse inserts a tube into a male’s pouch but she’s not retrieving sperm, just inserting eggs for the male to fertilize and carry to term. Some female scirtid beetles can push out a bit of the ducts leading to their sperm-storage organs, and female astigmatan mites extend a tube that is “quite long, actually,” Yoshizawa says. “The

Neotrogla

female penis is the spiniest.”

Neotrogla is a recent addition to the world’s known insect genera, described in 2010 based on specimens collected from harsh, dry caves in eastern Brazil explored by Rodrigo Lopes Ferreira of the Federal University of Lavras in Brazil. “They live in such a severe condition that only a few species can survive,” he says.

Aside from the wow factor of the insects’ anatomy, Schilthuizen calls the lice genital role reversal “important because it is the exception that proves the rule of sexual selection.” How much each sex invests in reproduction affects how choosy that sex is. If male cave lice are bundling a lot of their tiny sperm and extras into huge, nutritious packages in a nearly barren environment, the male could become the choosy one and the female the wanton and sexually more aggressive one.

Striking as the cave lice are, he says, “there are still so many unstudied insects out there that I wouldn’t be surprised if more examples turn up sooner or later.”

Editor’s Note: This story was updated on April 17, 2014, to correct how long the insects can spend in a single mating episode. It was further updated on May 9, 2014, to clarify that males in only three of the four Neotrogla species have genital pockets.