A jellyfish-like hydrozoan with a novel power to rewind its life cycle has been spreading rapidly around the world’s oceans without anyone taking much notice, researchers say.

The life history of Turritopsis dohrnii takes such twists and turns that only a new genetic analysis has revealed that the creature is invading waters worldwide, says Maria Pia Miglietta of Pennsylvania State University in University Park.

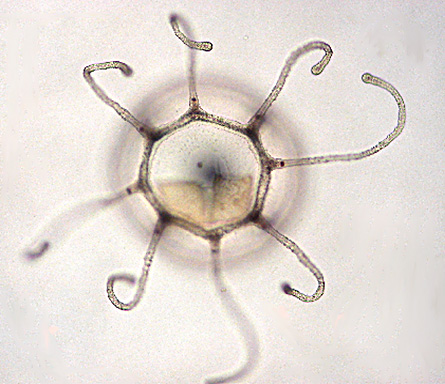

The first peculiarity of the seven species of Turritopsis had inspired biologists to describe these hydrozoans as “potentially immortal.” The adults form filmy bells reminiscent of their jellyfish relatives. When times get tough, faced with scarce food or other catastrophe, Turritopsis often don’t die. They just get young again.

Normally the organisms reproduce like grown-ups with sperm and eggs. In case of emergency, though, a bedeviled bell sinks down and the blob of tissue sticks to a surface below. There Turritopsis’ cells seem to reverse their life stage. When the blob grows again, it becomes the stalklike polyp of its youth and matures into a free-floating bell all over again. “This is equivalent to a butterfly that goes back to a caterpillar,” Miglietta says.

That’s a fine trick for surviving the strains of being swallowed in a huge gulp of water for a ship’s ballast and being hauled around the world, Miglietta says. The creatures can restart their life cycles right in the bottom of the ballast tank. Ballast water has become the major route for moving alien species from one ocean to another, and that’s probably what’s happening to T. dohrnii, Miglietta said June 21 in Minneapolis during the Evolution 2008 meeting.

DNA analysis of these reversible hydrozoans shows signs of recent travel, she said. She and colleague Harilaos Lessios of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute compared mitochondrial DNA from T. dohrnii collected off Florida and Panama with DNA sequences from around the world, analyzed and collected in previous studies. In this comparison, she found a group of very similar DNA sequences distributed from Panama to Japan, she reported. Within that lineage, 15 individuals had identical DNA in the stretch she sequenced, even though they came from Spain, Italy, Japan and the Atlantic side of Panama. To get that pattern, there’s been some fast travel going on.

Miglietta said that the DNA revealed a new peculiarity of the hydrozoan lifestyle, a sort of shape shifting that depends on where the individuals grow. Around Panama, the 259 adults she examined had eight tentacles. But in temperate waters, decades of observations have found higher, more variable numbers, such as 14 to 24 off Japan and 12 to 24 in the Mediterranean. Yet the work confirms the different forms belong to the same species.

As far as she knows now, Miglietta said, the hydrozoans aren’t disrupting the ecosystems they’re invading. But they do demonstrate how marine invasions can be difficult to understand.

That statement drew heartfelt agreement from John Darling of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s National Exposure Research Laboratory in Cincinnati. Genetics has also revealed hidden twists in a marine invasion he described at the Evolution meeting.

The Cordylophora caspia hydrozoans he studies, originally from the Ponto-Caspian region, don’t have a reversible lifestyle, but genetic differences may expand the species’ range of salt tolerance. Some colonize fresh water while others live in brackish water. Taxonomists now mostly call the invader one species regardless of water tolerance, Darling said, but his genetic analysis would support at least two species.