Images of little dots, some wriggling a skinny tail, give scientists a first glimpse of a vast swath of the oldest, and perhaps oddest, fungal group alive today.

The first views suggest that unlike any other fungi known, these might live as essentially naked cells without the rigid cell wall that supposedly defines a fungus, says Tom Richards of the Natural History Museum in London and the University of Exeter in England. He calls these long-overlooked fungi cryptomycota, or “hidden fungi.” Of the life stages seen so far, a swimming form and one attached to algal cells, there’s no sign of the usual outer coat rich in a tough material called chitin, Richards and his colleagues report online May 11 in Nature.

“People are going to be excited,” predicts mycologist Tim James of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, who also studies an ancient group of fungi.

Other research has indicated the new group exists, but the current study starts to reveal the biology. “The question is, is there another stage in the life cycle that does have cell walls?” he says.

By analyzing DNA pulled directly from the environment, Richards and his colleagues have confirmed that the hidden fungi belong on the same ancient branch as a known genus named Rozella. Although researchers have picked up DNA traces of fungi that didn’t quite fit in any group for at least a decade, the organisms (so far) won’t grow in labs. That in itself isn’t astounding for fungi, which can be difficult to culture.

As the researchers examined DNA sequences from databases, the ancient group “just got bigger and bigger [in genetic diversity] until it was as big as all previously known fungi,” Richards says.

Lakes in France, farms in the United States and sediment deep in the sea have all yielded DNA sequences in this group. The one habitat it doesn’t seem to like is open ocean, Richards says.

“The big message here is that most fungi and most fungal diversity reside in fungi that have neither been collected nor cultivated,” says John W. Taylor of the University of California, Berkeley.

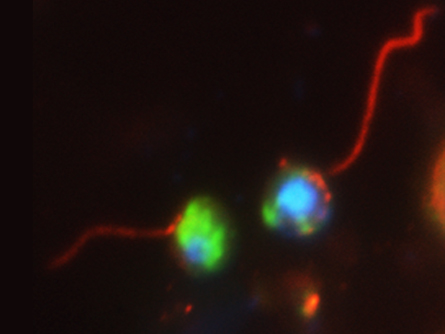

Exeter team member Meredith Jones spotted the hard-to-detect organisms by marking them with fluorescent tags. The trick revealed fungal cells attached to algal cells as if parasitizing them. One of the big questions about early fungi is whether they might have arisen from “some kind of parasitic ancestor like Rozella,” says Rytas Vilgalys of Duke University.

Interesting, yes. But loosening the definition of fungi to include organisms without chitin walls could wreak havoc in the concept of that group, objects Robert Lücking of the Field Museum in Chicago. “I would actually conclude, based on the evidence, that these are not fungi,” he says. Instead, they might be near relatives — an almost-fungus.