New test may improve pancreatic cancer diagnoses

Method relies on five proteins from bits of tumor circulating in blood

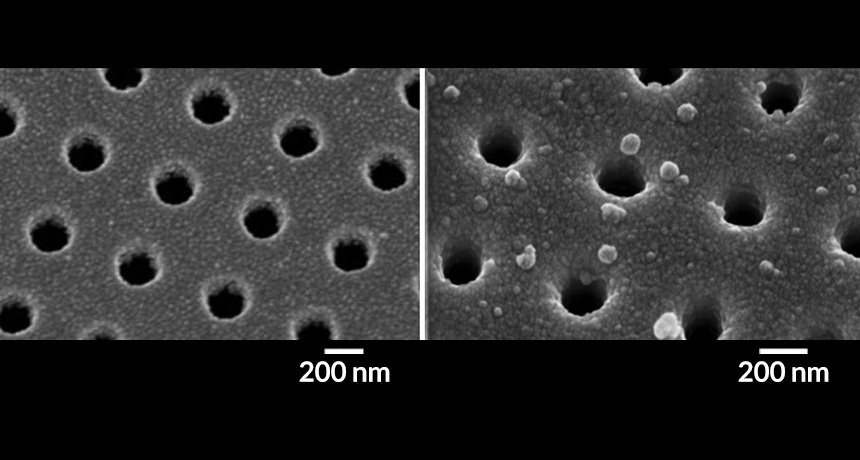

CHIP OF HOLES When an antibody-coated chip with nano-sized holes (left) binds proteins in extracellular vesicles (droplets in image at right) shed from pancreatic tumors, a sensor detects a shift in the wavelength of light shining through the holes.

K.S. Yang et al/STM 2017

Pancreatic cancer is hard to detect early, when the disease is most amenable to treatment. But a new study describes a blood test that may aid the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and someday make earlier screening feasible, the authors say.

The test detects a combination of five tumor proteins that appear to be a reliable signature of the disease, the researchers report in the May 24 Science Translational Medicine. In patients undergoing pancreatic or abdominal surgery, the test was 84 percent accurate at picking out those who had pancreatic cancer.

“What’s exciting about the study is that it further favors the belief that one biomarker by itself may not be able to successfully identify a disease,” says Raghu Kalluri, a cancer biologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who was not involved in the study. By putting the five protein biomarkers together, he says, “the power of the analysis might be more beneficial in differentiating healthy individuals and ones with pancreatic cancer.”

The National Cancer Institute estimates that in 2017 there will be more than 53,000 new cases of pancreatic cancer in the United States and just over 43,000 deaths from the cancer. Individuals with the most common form of pancreatic cancer, called pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, have a five-year survival rate of less than 10 percent. The cancer is usually caught late because the symptoms, including weight loss and abdominal pain, often don’t arise until the cancer has spread. And current imaging technology can’t detect the cancer at the start, says study coauthor Cesar Castro, a translational oncologist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“The unmet need here is finding some other form of detection before a cancer grows large enough for the CT scan to detect it,” Castro says.

In their hunt for better detection methods, the researchers turned to tumor-derived extracellular vesicles, small sacs shed by tumor cells that circulate in the bloodstream. The sacs “are almost like mini-mes” of the parent tumor, Castro says, because they contain proteins and genetic material that often match the tumor.

The researchers selected five promising protein biomarkers from tumor-derived extracellular vesicles. Using a gold-coated silicon chip covered with antibodies and sporting nanopores, the team tested how well the biomarkers signaled the presence of pancreatic cancer in plasma samples from patients. When light shining through the pores encountered the extracellular vesicles, bound to the chip because of the interaction between the protein biomarkers and the antibodies, the light’s wavelength changed — signaling the presence of a tumor.

In plasma samples taken from 43 patients before scheduled surgery for a medical issue in the pancreas or abdomen, the panel of five biomarkers distinguished pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma from pancreatitis — an inflammation of the pancreas — and from benign cysts as well as from control patients’ samples. A pathology report after the surgeries confirmed the results.

Using their sensing device, the researchers report that the combined five biomarkers correctly identified whether a patient had pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma or not in 84 percent of cases. The highest accuracy for any one of these biomarkers used by itself was just 70 percent.

The next step is to test patients at high risk for pancreatic cancer, and eventually those who are healthy, to see if these biomarkers are effective at early screening. “What we need to do now is pivot towards precancerous lesions,” Castro says. “Can they pick up any precancerous changes?”

“I’m excited about anything that can happen for these patients who are in desperate need for biomarkers and treatment,” Kalluri says. But he cautions that studies reporting the effectiveness of biomarkers as cancer screening tools often use different technologies for their assessments, making it hard for academic laboratories to reproduce the results. “There’s a tremendous lack of organized effort in the biomarker field,” he says, and if there is no way to come to a consensus on which biomarkers are most promising, “it’s very difficult for a patient to realize any benefit.”