A team of astronomers has spotted Hermes, an asteroid that disappeared into the night after a close flyby of Earth in 1937. Ever since, some researchers have wondered–and worried–about the asteroid’s path. Last month, scientists finally found Hermes, and they now know what to expect from it.

“Within the astronomical community, people were almost obsessed with finding this thing,” says Tim Spahr of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Mass.

Early in the morning of Oct. 15, Brian Skiff of Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz., spotted a possible near-Earth asteroid. He alerted Spahr, who posted the finding on the Internet. Observers in California saw the asteroid within 30 minutes and sent additional positional data to Spahr.

Reviewing recent images of the sky, he could follow the asteroid and make rough calculations of its orbit around the sun. The trajectory he came up with convinced him the asteroid was Hermes. Within hours of the original sighting, Spahr announced Hermes’ reappearance in an Internet circular of the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

“We’ve kind of expected that it could be found sooner or later,” comments Alan Harris of the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo. “We’ve been waiting, and finally they’ve got it.”

The precise calculation of Hermes’ path through space was made by Steven Chesley and Paul Chodas of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Usually, astronomers there use programs to predict whether or not an asteroid might slam into Earth. In this case, Chesley and Chodas ran such a program backwards to determine Hermes’ path for the past 66 years.

They calculated that the asteroid made 31 unobserved circuits around the sun during this time. Six times, Hermes must have come within 9 million kilometers of Earth, or 24 times the Earth-moon distance. In 1942, Hermes came within 640,000 km, a mere 1.6 times the distance to the moon.

This year, Hermes will be at its closest–a comfortable 7 million km away–on Nov. 4. By extrapolating the orbit into the future, the astronomers verified there’s no chance of Hermes hitting Earth within the next 100 years, which is as long into the future as astronomers typically predict for asteroids.

Hermes is “fairly large and capable of making close approaches to Earth,” says Spahr. “It’s nice to know where it is now.”

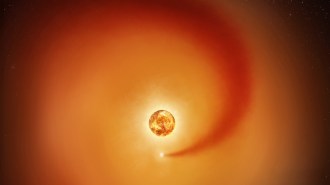

Beyond knowing Hermes’ orbit, researchers were interested in the asteroid itself. Using the Arecibo Radar Telescope in Puerto Rico, Jean-Luc Margot of the University of California, Los Angeles was able to tell that Hermes consists of two gravitationally tied pieces, each about 300 to 450 meters across and orbiting the other.

“What was particularly surprising was that it was a binary with equal components,” says Margot, who presented the finding in an Oct. 20 IAU circular. Most binary objects have a primary body with a smaller satellite, he says. The unusual arrangement could help astronomers better understand how asteroids break into two and how one component influences the motion of the other.

****************

If you have a comment on this article that you would like considered for publication in Science News, send it to editors@sciencenews.org. Please include your name and location.

To subscribe to Science News (print), go to https://www.kable.com/pub/scnw/

subServices.asp.

To sign up for the free weekly e-LETTER from Science News, go to http://www.sciencenews.org/subscribe_form.asp.