These snails give live birth, and it’s the babies that may do the labor

Protecting eggs in mom’s body may have given periwinkle snails an advantage over egg-laying cousins

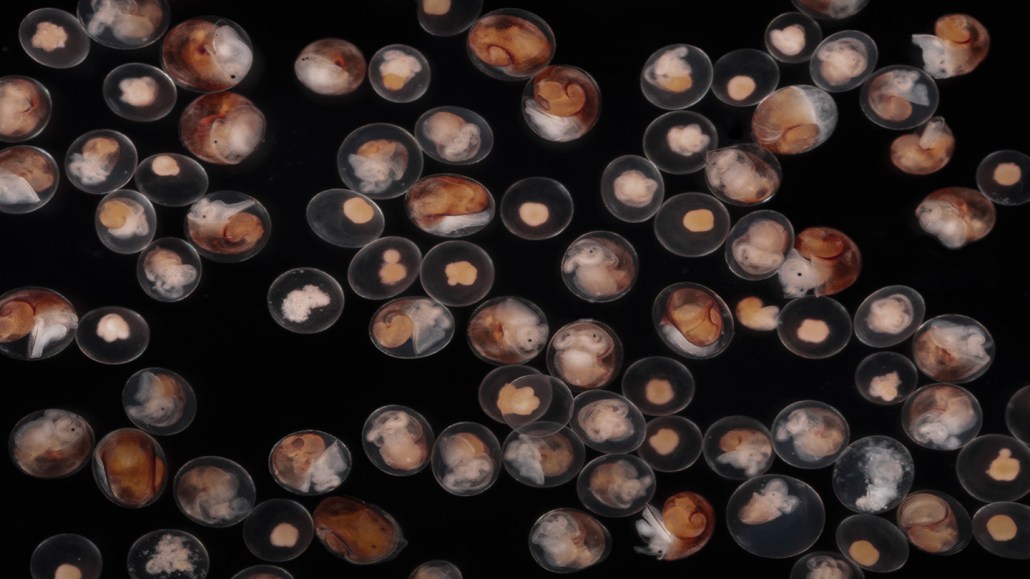

In rough periwinkle snails, embryos form and mature inside the brood pouch at different rates, as seen here. When it’s time to hatch, youngsters may have to crawl out of mom’s body and into the world on their own.

FREDRIK PLEIJEL

The oddball minority of animals that don’t lay eggs includes a tough little snail called a rough periwinkle.

Unlike mammals giving birth to kittens and fawns and helpless little humans, this tidal-zone snail has switched to live birth relatively recently. Its newcomer version of birthing offspring into the world without an eggshell is…. different: These periwinkle moms give birth multiple times a day. And unlike humans, it’s probably not the mom but the babies who do the hard labor.

Egg-laying periwinkle relatives have a jelly gland that creates a goo-protected mass of eggs outside the mom’s body. But in Littorina saxatilis, the gland has evolved into a make-do womb, or brood pouch. Eggs still form there, but stay inside mom’s body until after they hatch, says evolutionary ecologist Kerstin Johannesson of the University of Gothenburg in Sweden.

Mom can have up to a few hundred embryos at various stages of maturation in the gland. When birthing the mature ones, “if she starts to push, also the ones that are not ready will probably come out,” Johannesson says. As a long-time observer of the snails, she doubts that the moms push at all. The little periwinkles may crawl out of their mother’s body and into the world on their own.

When ready to leave the mob in the brood pouch, each baby snail first scrapes a hole in its own transparent eggshell-like covering, “like a hatching bird,” Johannesson says. Then babies must find the exit from mom’s body. “How they find it, we do not know,” she says, “but maybe they can feel the smell of fresh saltwater coming from the outside through the hole.”

The live birth of these snails fascinates Johannesson and others because the species probably developed the ability in the last 100,000 years or so. That’s just an evolutionary eyeblink, really.

When comparing rough periwinkles with two close sister species (L. arcana and L. compressa), the only reliable visible difference that shows they are separate species is the quirk of live birth.

It was glass German Christmas ornaments that helped evolutionary biologist Sean Stankowski clarify just how strong a species barrier separates live bearers from egg-laying sisters. The glass ornaments, made to be filled with chocolates and dangled on a holiday tree, worked well as passion chambers for pairs of snails, one partner from a live-bearer species and one from an egg-layer. (Considering mollusks in general, this had the kink of pairing males with females rather than the normal two hermaphrodites lining up for mutual sperm delivery.)

In the glass ornaments, some of the pairs mated. But Stankowski, of the University of Sussex in England, and colleagues found no viable offspring, a sign the partners are separate species, in this case with strong separation. Ability to make babies is one way to think about defining a species, but far from the only way (SN: 10/31/17).

The ornaments were just a tiny part of some seven years of intense research, mostly genetic exploration, that let Stankowski, Johannesson and colleagues explore how an egg-laying lineage gave rise to such a consequential change as live birth. Both L. arcana and L. saxatilis live in the drown-dry craziness of rocky tidal zones, but the egg-layers stay mostly in northern Europe and Russia. The live-birth species, however, has spread farther around Europe and added the northern Atlantic coast of North America to its range. Because L. saxatilis hitchhikes well, it now lives in San Francisco Bay and the canals of Venice.

Yet live birth doesn’t look as if it came from some big dramatic genetic change. Instead, differences built up bit by bit, from changes in some 50 regions in the snail’s genes. None of these seems more influential than any of the others, the team reports January 5 in Science.

Giving the eggs more protection might explain the species’ success, the researchers say, even though the newborns emerge from their moms looking vulnerable and only half a millimeter long. You can feel them between your fingers “like grains of sand,” says Johannesson. “They simply creep out of the mother’s pocket, and quite often you can see them crawling around on her shell.” Mom may not help her offspring emerge, but she can provide their first breakfast: diatoms and bacteria ready to be scraped off her shell. Nom-nom!