It can be a robot-eat-bee world out there, but bumblebees can learn to outwit electronics that mimic lurking spiders.

Getting wise to the dangers of camouflaged predators, however, has a cost for the bees, says Lars Chittka of Queen Mary, University of London. Predator-savvy bees get jumpy, slowing down on the nectar-collection job, he and a colleague report in an upcoming Current Biology.

And in the end, some of the bumblebees get a little paranoid, increasingly shying away from safe flowers. “They’re behaving as if they’re starting to see ghosts,” Chittka says.

Bees may not have particularly big brains, but they manage some sophisticated behavior. They make good subjects for studying how an animal’s learning capacity affects how it makes a living, he says.

To see what bees can learn about the tricks of their predators, Ings and Chittka focused on crab spiders, which lurk in flowers to hunt pollinators and can change color over the course of several days to match petals. That is, as long as the petals are yellow, white or, for some crab spider species, pink.

In the real world, the big, hard-bodied bumblebees with plenty of flight power represent a considerable challenge for crab spiders. Most of the time, the bee escapes from the attack and has a chance to learn, Ings says.

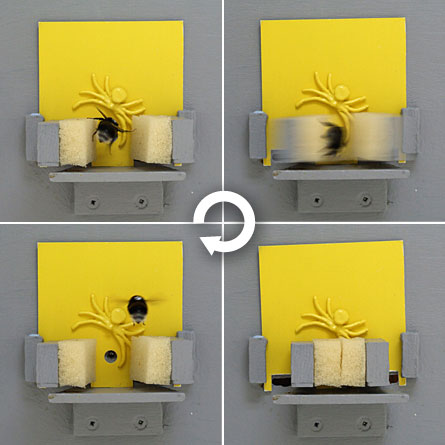

For simulating a near-death experience with a Misumena vatia crab spider, Ings and engineer consultants took inspiration from the pincers that brake a bicycle wheel. Ings worked out an electric switch with a little pair of arms that he could trigger remotely to close on a visiting bee. He cushioned the jaws with strips of household cleaning sponges, and for the full treatment, positioned a life-size plastic crab spider in a plausible color just above the pincers.

“The robotic spider is fantastic,” says another crab-spider researcher, Marie Herberstein of MacquarieUniversity in Sydney, Australia. This invention offers much better experimental control than handheld squeezing tools researchers’ used in earlier experiments, she says.

Ings and Chittka trained the bumblebees to buzz around an array of 16 floral-yellow rectangles, each equipped with a pair of pincers and a hole between the pincers’ jaws for sipping droplets of sugar water.

For the learning tests, the researchers positioned spider models, either a high-contrast white or camouflaged yellow, on four randomly selected yellow rectangles. Each bee saw only one kind of spider. Ings immobilized any bee that landed between the sponge jaws of these infested rectangles.

Surprisingly, the camouflage didn’t make any difference in the number of visits bees needed to learn to avoid spiders, Chittka says. He sees an evolutionary arms race between the two adversaries, and “now the advantage is to the bees,” he says.

Camouflage did have its effects though. The researchers discovered that bees exposed only to camouflaged spiders slowed down, as if sacrificing speed for accuracy in investigating a flower. These bees hovered in front of a rectangle an extra few tenths of a second. But bees that had only seen the white-on-yellow spiders made their decisions faster.

Camouflage also raised the risks of getting spooked and fleeing a rectangle that actually had no spider. These false alarms showed up most dramatically when the researchers tested bees 24 hours after training.

The rise in false-alarm rates after a night’s sleep parallels a phenomenon known from studies of human memory. “Memories don’t just fade, but change with time,” Chittka says. Traumatic memories can even intensify. Researchers working with nonhuman animals often haven’t taken into account the many ways memory can morph after an experience, Chittka says.

Interesting as the robot is, it doesn’t mimic spider movement or allow bees to check out its profile from both sides. “This opens the door to a whole range of questions about what really goes on in the field,” says Jér´me Casas of the University of Tours in France.