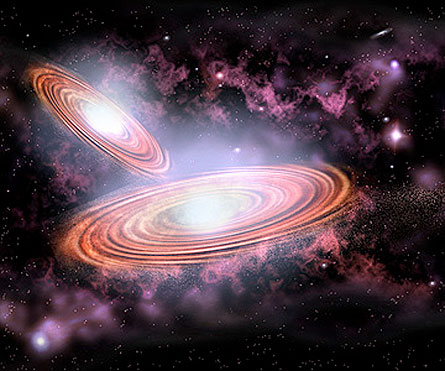

Two astronomers may be seeing double. They report evidence that a galaxy about 4 billion light-years from Earth houses not one, but two giant black holes. Moreover, the duo might be separated by only one-third of a light-year — less than 10 percent of the distance between the sun and its nearest star system, Alpha Centauri.

Todd Boroson and Tod Lauer of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory in Tucson caution that their findings are preliminary. “This is a candidate, not a proven, binary black hole,” Lauer emphasizes. But if further observations support the discovery, it would be the most tightly bound pair of giant black holes ever found, the researchers report in the March 5 Nature.

Models suggest, and observations have revealed, that most massive galaxies house a massive black hole at their core. In addition, galaxies often grow bigger by merging. In theory, then, pairs of closely orbiting black holes ought to be common, but in practice they’ve been hard to detect.

Boroson and Lauer analyzed the spectra of about 17,500 quasars — the brilliant beacons of light believed to be fueled by supermassive black holes — recorded by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. The team was looking for signs of black hole pairs, and one quasar, dubbed SDSS J153636.22+044127.0, fit the bill.

The spectra of gas orbiting the quasar show two broad peaks of visible-light radiation. The broadness indicates that the gas is moving at high velocity, as would be expected if the material were closely orbiting a black hole. The twin peaks strongly suggest this quasar lies within a galaxy housing two supermassive black holes, the team says. One of the black holes would weigh the equivalent of about 50 million suns, the other about 20 million suns.

Other features in the spectra indicate that there’s only a 0.3 percent chance that the researchers were fooled by the chance superposition of two separate galaxies, Lauer notes. Such a superposition ought to show up in images to be taken with the Hubble Space Telescope, Lauer says. “If we see two nuclei, then our model is incorrect,” he notes.

But the best way to confirm the find is to take more spectra, he adds. If the team has found two black holes that lie close to each other, then the velocity of the smaller black hole, as seen from Earth, ought to vary on a time scale of just a year or so as the body orbits the bigger black hole. Careful monitoring of the spectra would reveal such a trend.

Astronomer Greg Taylor of the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque cautions that several other galaxies showing a pair of broad emission lines have turned out to house just a single black hole. In those cases, the two peaks were generated by jets of gas that interacted with material surrounding the lone supermassive black hole at the galaxy’s core.

In 2006 Taylor and his colleagues reported finding solid evidence of a pair of black holes 24 light-years apart. Those researchers used the Very Long Baseline Array, a continent-wide array of radio telescopes, to directly image the radio waves associated with each black hole in the galaxy 0402+379. Taylor and his colleagues report new details about their discovery in an article recently posted online (http://arxiv.org/abs/0902.4444) and set to appear in an upcoming Astrophysical Journal.

To nail down the new result, Taylor suggests using the same array to look for a pair of radio-emitting objects in the galaxy studied by Boroson and Lauer.