Unknowns about Zika virus continue to frustrate

Public health officials race to find answers, develop a vaccine

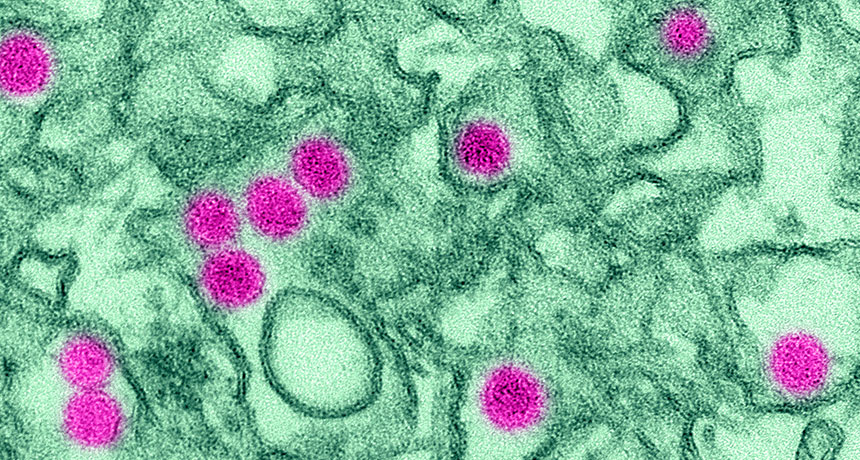

GOING VIRAL Zika virus (shown in this false-color transmission electron micrograph) continues to spread across the Americas, and may be linked to a recent rise in birth defects in Brazil.

Jessica Wilson/Science Source