Valuing Nature

When economic payoffs justify conservation

Around the edges of the Mabira Forest Reserve in Uganda, farms and woodlands are locked in a battle, and the woodlands are losing ground. Scores of bird species face an increasingly desperate situation. Yet according to a new economic study, most of them could be saved. By attracting enough tourism revenue to justify the preservation of their habitat, the birds just might rescue themselves.

Ecotourism—as well as hunting, fishing, timber harvesting, and other human activities—requires nature. Healthy ecosystems provide a range of public services, too, such as water purification, greenhouse-gas absorption, and protection from coastal-storm surges.

Ecological conservation could safeguard those benefits. But financial markets generally don’t encourage or reward conservation. To correct what some economists, scientists, and government officials view as an oversight, they have taken steps toward commercializing nature’s goods and services.

The latest example of this approach is the study in the Ugandan forest reserve, conducted by Robin Naidoo of the World Wildlife Fund in Washington, D.C., and Wiktor L. Adamowicz of the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

“There is a certain cost to preserving this forest because the forest could be used in other ways, [namely for] agriculture,” says Naidoo. “But there’s also a certain benefit generated from the income from tourism.” His team calculates that more than half the park is more valuable in its current state than it would be as farmland.

Paying the price

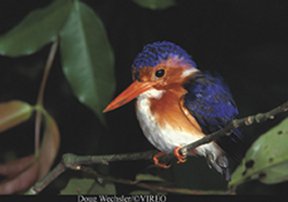

The white-bellied kingfisher, the joyful greenbul, the papyrus gonolek, and about 140 other bird species attract about 4,000 foreigners to Mabira each year. The tourists spend money on transportation, accommodations, and food, and pay park-entrance fees amounting to $9,500 a year.

Naidoo and Adamowicz set out to compare the park’s potential to generate entrance fees with the land’s commercial promise if it were put under the plow. They used satellite images and other data to assess the potential of different segments of land.

Even if the more fertile half of the area within the reserve were converted to farmland, the remaining forest would be large enough to support about 115 bird species—enough to keep many tourists coming, the researchers calculated. “You can protect 80 percent of the bird species just from the entrance fees,” Naidoo concludes.

The researchers also had their assistants interview 861 foreigners who were on their way out of Uganda, via its international airport. From that survey, the team attempted to gauge the foreigners’ willingness to pay to see wildlife, taking into account such factors as the animals’ abundance and diversity.

A more-than-tenfold increase in the reserve’s entrance fee, to $47 per foreigner, would maximize revenues, the researchers report in the Nov. 15 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The income from such a fee would outweigh the potential agricultural value of about two-thirds of the 300-square-kilometer reserve and would protect 90 percent of the bird species.

“Nature can be worth a huge amount to us,” says Stuart L. Pimm of Duke University in Durham, N.C. The new study nicely demonstrates that value, he says, although it doesn’t grapple with certain critical details, such as whether park revenue gets injected into the local economy. If the money gets spent elsewhere, he and Naidoo agree, the incentive for neighboring communities to protect rather than farm Mabira’s land would disappear.

“Just the ecotourism benefits from this forest are enough to protect a good portion of the forest,” observes ecological economist Robert Costanza of the University of Vermont in Burlington.

Most services provided by nature are difficult to appraise and sell, Costanza says. In 1997, he and his colleagues estimated that the world’s ecosystems render products and services worth from $18 trillion to $61 trillion per year.

Costanza and others aim eventually to create financial markets for many ecosystem services, making conservation widely profitable. First, however, they are working to identify regions of the world that generate abundant benefits. In 2002, Costanza and Paul C. Sutton of the University of Denver estimated that some nations, including Uganda, produce 10 times as much economic value through ecosystem services as through all commerce in the country.

Now, researchers with the World Wildlife Fund are collaborating to map the value of ecosystem services in the specific regions of the world. Costa Rica has already commercialized some of the ecosystem services rendered by its forests, such as attracting ecotourism and maintaining clean water supplies. For example, the government collects water-use fees from hydroelectric plants and urban residents. Funds then flow to landowners who conserve forests.

“The conventional economic wisdom was, ‘The environment is a luxury good,'” Costanza says. That philosophy suggests that only a wealthy society can afford to preserve nature, he says. “The reality is just the opposite. The environment is humanity’s life-support system. Once you make that paradigm shift, a lot of other things fall into place.”