Compared to slaying dragons or building civilizations, figuring out the shape of a protein doesn’t sound particularly thrilling. But turn the task into an online game, replete with the competition and camaraderie of “World of Warcraft,” and the masses will come.

More than 57,000 people, many of them nonscientists, got involved in Foldit, a game geared towards solving the puzzle of protein structure, researchers report in the Aug. 5 Nature. And several top-ranked players outdid state-of-the-art computer algorithms that tackle the same tasks. The project suggests that online games tapping into the wisdom of crowds may be a fruitful approach to scientific challenges.

“Humans have all sorts of creativity, problem-solving skills and insights,” says study coauthor Seth Cooper of the University of Washington in Seattle. “Hopefully other problems can be cast in this way so people without formal training can still get involved and help out.”

Making games of mundane tasks such as cleaning is a trick familiar to most babysitters. Applying that strategy to one of science’s long-standing challenges is “really cool,” says Stanford University’s Nick Yee.

“The mere acts of giving people points for doing something and pitting people against each other are huge motivators,” says Yee, who studies the sociology of online games. “Dress a tedious task in the guise of a game, and there are players who will spend hours and hours on end doing a task they wouldn’t otherwise do.”

Foldit, the game created by Cooper and his colleagues, tackles the protein-folding problem, one that has long vexed science. Proteins are the building blocks of much of life and are its movers and shakers — they make reactions go, send signals between cells and partake in a suite of other tasks.

Each protein starts as a string of amino acids and must fold into its particular 3-D structure before it can do work. Scientists know that a protein’s final shape is determined by the sequence of its amino acid building blocks. But predicting that final structure from the amino acid sequence alone is extremely difficult.

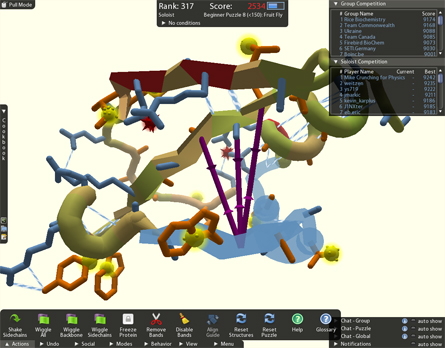

Foldit recruited the online community to tackle the problem. Players tweak, tug and twist partially folded proteins, with the aim of reaching 3-D structures that are energetically comfortable for the protein to maintain. Foldit has a good mix of the three main motivators in online gaming: competition (players score points and are ranked), camaraderie (teams can play, sharing strategies and dividing labor) and immersion (players can lose themselves in the game). It also provides “bridges” between those motivations, skirting player boredom and burnout.

“I’m a self-confessed hopeless addict; in seven months I’ve missed only two days. But every day, and in every way, I’m getting better,” said one Foldit player in an informal survey conducted by the researchers.

Top players — many of whom had little or no formal biochemistry background — outperformed Rosetta, an automated computer algorithm designed to figure out protein structure. Players were willing to push through conformations that were energetically lousy to get to a good conformation on the other side — a strategy that an algorithm won’t take, Cooper says.

Foldit was such a success that the University of Washington is starting a new center for game science, Cooper says. Perhaps many scientific problems — especially spatial ones — can be tackled en masse online.

“The word game has been kind of a bad word,” says Yee. “Computer games are just trivial; they’re what teenagers do in their basement. This paper shows you can actually use computer games to solve really hard problems.”