Dazzle camouflage may fool a locust

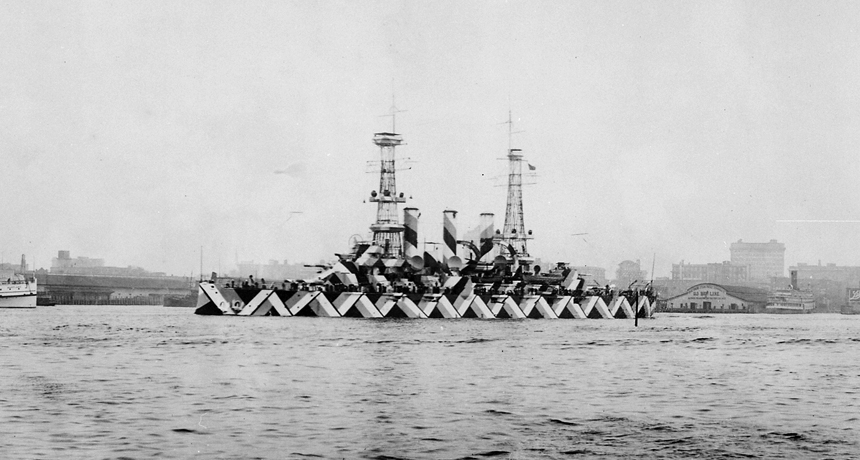

During World Wars I and II, some U.S. and British naval vessels, such as the U.S.S. Nebraska, shown here in 1918, were painted in a type of camouflage known as dazzle painting. Though evidence is scant that humans are fooled by the camouflage, a new study suggests that dazzle patterns do confound locusts.

U.S. National Archives and Record Administration/Wikimedia Commons