Antimatter hydrogen has the same quantum quirk as normal hydrogen

Physicists detected a subtle effect in antihydrogen known as the Lamb shift

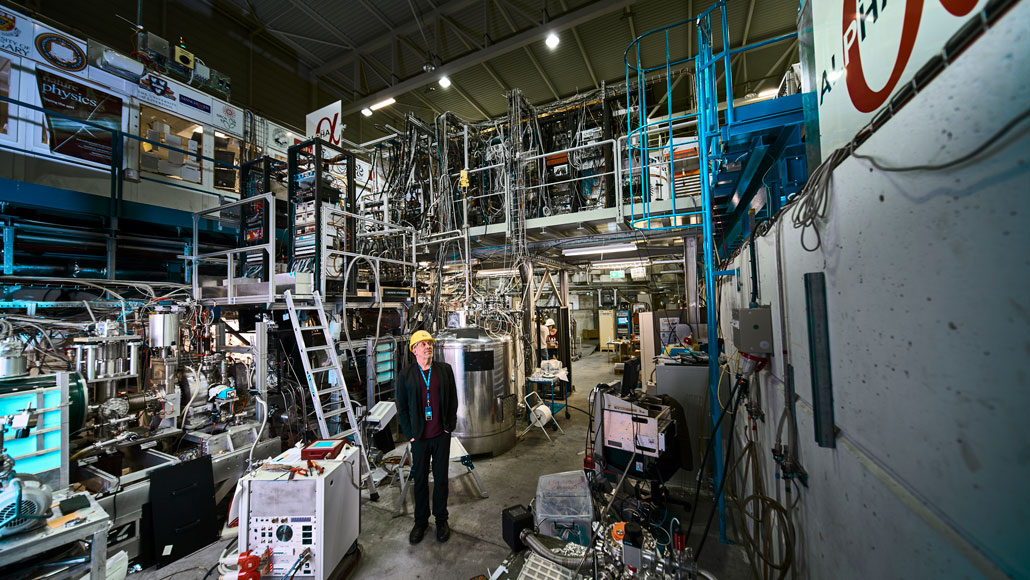

Scientists with the ALPHA experiment (shown) report that they’ve found a quantum effect called the Lamb shift in antimatter hydrogen atoms.

Maximilien Brice, Julien Ordan/CERN