The antiviral drug Paxlovid reduces the risk of getting long COVID

It’s not a panacea, but it might be one of the things that can help

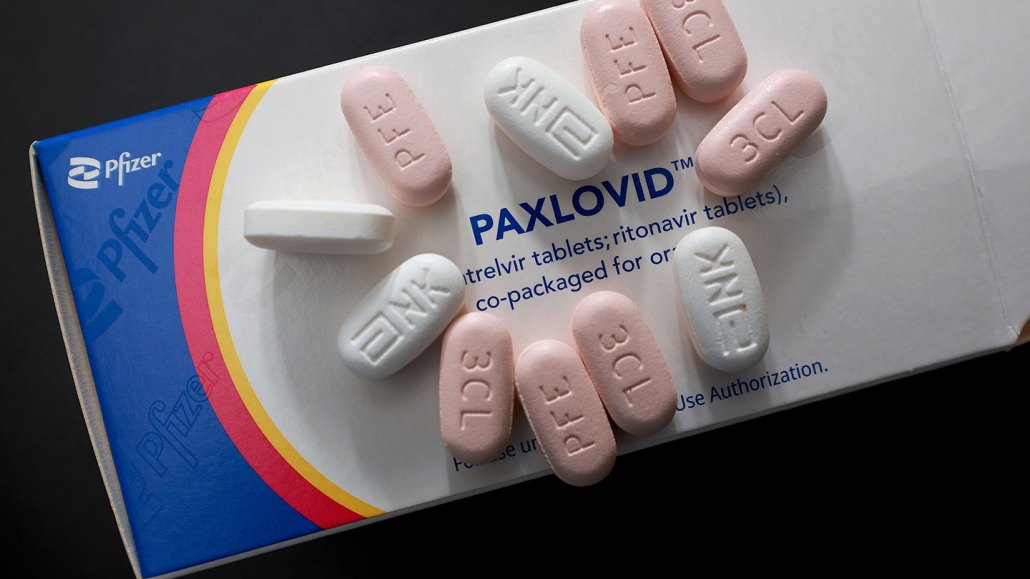

Paxlovid, an antiviral drug that stops the coronavirus from replicating, might protect against long COVID.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images News

The antiviral medication Paxlovid seems to reduce the chance of developing long COVID, researchers report.

In a large study of veterans’ medical records, Paxlovid lowered a person’s chance of landing in the hospital or dying from all causes in the six months following a COVID-19 infection. And the drug reduced the risk of developing 10 of 13 long-term health problems, researchers report March 23 in JAMA Internal Medicine. On average, the drug lowered the relative risk of developing the conditions by 26 percent, says Ziyad Al-Aly, a clinical epidemiologist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

The antiviral drug provided protection against some heart problems, blood clots, kidney damage, muscle pain, fatigue, shortness of breath and two neurological conditions. But it did not lessen the chance of developing liver disease, cough or of getting diabetes after a COVID infection (SN: 1/4/22).

Paxlovid, made by the pharmaceutical company Pfizer, has previously been shown to reduce the chance that susceptible people will be hospitalized or die from COVID (SN: 1/11/22)). To assess the drug’s longer-term effects, Al-Aly and colleagues examined medical records from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ health care system. The researchers found more than 280,000 patients who had a positive COVID test in 2022 and at least one risk factor for developing severe illness. Of those people, nearly 36,000 got Paxlovid within five days of their positive test result.

The team then compared the health outcomes of those who took Paxlovid with those who did not. Since omicron and its subvariants were circulating in 2022, the researchers compared people in the Paxlovid group only with people in the untreated group who were infected at the same time and in the same geographic region, Al-Aly says. Paxlovid takers had a reduced risk of post-COVID conditions regardless of whether the infection was their first or if they’d had prior bouts with earlier variants. The drug also lowered long COVID risk for unvaccinated people, for those who were vaccinated with one or two doses, and for people who had at least one booster shot.

Some researchers dispute whether the study fully captures what long COVID is. The condition is notoriously hard to define (SN: 7/29/22). “Even in research studies in which we have hours to ask questions, figuring out who has long COVID and who does not is challenging,” says Steven Deeks, a long COVID researcher at the University of California, San Francisco. “These electronic medical record reviews are helpful, but they lack specificity for long COVID. They are great for studying other long-term consequences [of COVID], including cardiovascular events and strokes.”

For instance, many people with long COVID experience post-exertional malaise, or extreme tiredness after exercise, says Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, director of the post-COVID recovery clinic at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. But there isn’t a medical code for that condition, she says, “so it’s hard to pull out of a medical record review.”

Still, the study was able to identify some of the conditions that affect many people with long COVID, including dysautonomia, a condition in which the nervous system has trouble regulating heart rate, blood pressure and breathing.

And the large number of people in the study allows researchers to see effects they might not be able to uncover in smaller randomized control trials, Deeks says. “You can overcome bad data with huge numbers,” he says. In such large studies, “when you do see something, it tends to be real.”

One limitation of the study is that most patients in the Veterans Affairs system are white males, whereas long COVID patients tend to be female, says Al-Aly, who is also the chief of research and development at the VA St. Louis health care system. But he defends the study’s relevance to multiple populations. The study has “literally tens of thousands of women,” he says. “Is it true that the majority are male? It’s true, but you cannot deny the experience of tens of thousands of people just because they’re the minority.”

Paxlovid — as well as other antiviral drugs, vaccination and perhaps a diabetes drug called metformin — might all help protect against long COVID, but plenty of patients who have taken Paxlovid are still showing up in long COVID clinics (SN: 10/24/22).

“We know it’s not this panacea. It’s not going to be a miracle cure for long COVID,” Verduzco-Gutierrez says. “It may be one of the things that can help, or that can decrease the risk, but it’s not going to take it away completely.”