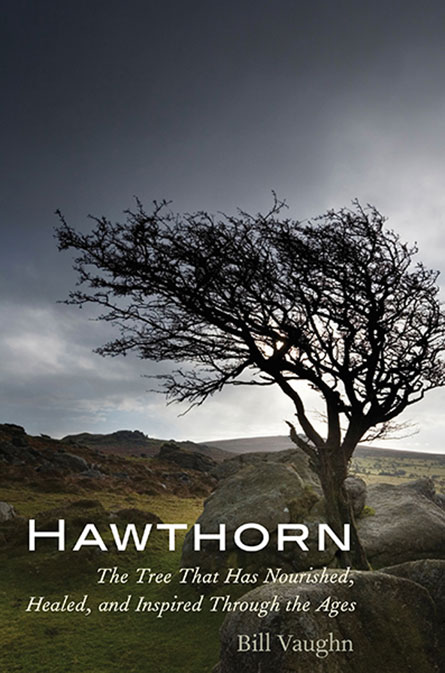

Hawthorn hedges, such as this one in England, have played an outsized role in history.

David Hawgood/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Hawthorn

Hawthorn

Bill Vaughn

Yale Univ, $30.00

It’s a testament to doggedness that people through the centuries have extracted any benefit at all from the hawthorn tree. It’s a gnarly, unforgiving thing with spikes. It takes real persistence and thick gloves to domesticate. In some places, hawthorns are considered giant weeds. A dense thicket of the bushy trees calls to mind the supernatural hedge that encircled Sleeping Beauty for 100 years.

“A hawthorn is not a tree most people want to hug,” writes Bill Vaughn, a writer and graphic artist.

But he shows in Hawthorn that outward drawbacks conceal attributes that people have exploited for centuries in iron-forging, weaponry, medicine and above all, the growing of hedgerows. This jack-of-all-trees story makes for a compelling read, spiced with arcane history and Vaughn’s own anecdotes.

For starters, readers learn that hawthorn wood is extremely hard and dense. Hawthorn burns hotter than oak or beech and provides ideal charcoal for blacksmith forges — and sword making. Hawthorn branches also snap back into position after flexing, thanks to the wood’s fibrous nature. Eastern Native Americans prized it for bows.

There are many species of hawthorn, all in the genus Crataegus. Its fruit, the haw, can range from tasty to arsenic-laden. Native Americans found medicinal value in the haw and other parts of the tree, and studies suggest haw extract can protect against heart failure. Chinese medicine recommends it for digestive ailments.

But hedging has been the crowning achievement of hawthorns. Growing an impenetrable hedge requires skill and patience. Hawthorns are planted and when half-grown, they are “pleached” — gashed partway across the trunk and bent over, inducing them to become a thicket. With other standing trees, hawthorns form the thorny rebar of a living fence, keeping livestock in and predators out.

Hawthorn hedgerows still grow in the green pastures of Normandy and England. The French hedgerows were so high and dense that Allies invading in 1944 needed to weld sharp steel blades on tanks to pierce the barriers.

A century earlier, hedgerow science that had focused on European hawthorns had found its way to the Great Plains of North America. Farming there had stalled because settlers lacked access to wood to fence off crops from livestock that would eat them. Vaughn, in one of many readable tangents, reveals that the best hedgerow plant for the Plains wasn’t a hawthorn but rather the native Osage orange, a thorny tree that rarely rots and is immune to termites. By 1895, Kansas alone had 72,000 miles of hedgerow.

But the adoption of barbed wire in the late 1800s doomed hedgerows in the Great Plains. The trees died, as did their ability to protect against the wind. Vaughn doesn’t say whether Dust Bowl farmers rued their missing hedgerows years later, when winds blew away their topsoil.

Buy Hawthorn from Amazon.com. Sales generated through the links to Amazon.com contribute to Society for Science & the Public’s programs.