Atom & Cosmos

Jupiter's bold stripe is back, plus more in this week's news

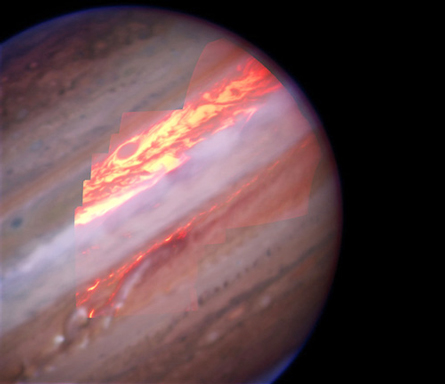

Jovian stripe reappears

New infrared images of Jupiter reveal why one of the giant planet’s most distinctive features, a brown-red stripe just south of the equator, is reemerging after being covered in white for about a year. The images, taken at the Keck observatory atop Hawaii’s Mauna Kea by Mike Wong of the University of California, Berkeley, show that wispy, high-altitude ice clouds that had formed over Jupiter’s southern region are now thinning, allowing more of the stripe to be seen. The Keck observatory released the images on February 9. —Ron Cowen

Life on rogue planets

Some planets that have been ejected from their solar systems and set adrift in the chill of interstellar space — a relatively common occurrence — might still be capable of supporting life, a study suggests. University of Chicago astrophysicists simulated a hypothetical lone planet with a composition similar to Earth’s but about 3.5 times heavier. Two internal sources of energy — the heat left over from the planet’s formation and the decay of radioactive elements — could maintain a liquid ocean for 1 billion to 5 billion years beneath a layer of insulating ice, the scientists calculate in a study posted online at arXiv.org on February 6. —Ron Cowen

Scientists have finally determined how (and where) speedy solar wind electrons snatch their tremendous energy during one kind of space weather storm. U.S. and Chinese researchers report online January 30 in Nature Physics that these electrons start off slow when first directed toward Earth by the planet’s outlying magnetic field, but then speed up as they near. The electrons appear to accelerate when changing magnetic fields closer to the planet send them corkscrewing. The conclusion matches theories proposed in the 1980s and should help scientists understand auroras and how the sun affects space weather near Earth. — Camille Carlisle