Bacteria help themselves in damaged lungs

Detailed understanding of how unusual bacteria survive could help treat deadly infections that plague cystic fibrosis patients

SAN FRANCISCO — Researchers have discovered that antibiotics made by Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria also serve as molecular snorkels that help the bacteria breathe even when buried in mucus or squeezed into the middle of a colony.

The finding was reported by MIT researchers Lars Dietrich and Dianne Newman December 16 at the annual meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology. It reveals a new role for antibiotics produced by bacteria, which scientists previously believed were mainly employed to fend off other bacteria.

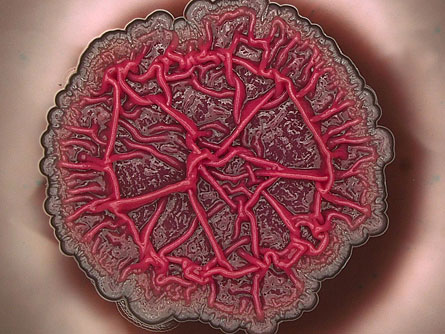

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a pathogenic bacteria species that is harmless to most healthy people. But for people with cystic fibrosis — a genetic disorder that leads to a buildup of thick, sticky mucus that clogs the lungs and digestive tract — the bacterium is deadly. P. aeruginosa invades the mucus, turning it blue-green with antibiotic pigments called phenazines and even destroying lung tissue.

The new study reveals that the molecules also help P. aeruginosa breathe and can act as communication molecules that help shape how communities of the organism grow. Drugs that disrupt the multitasking molecules might provide new treatments for cystic fibrosis patients, the team suggests.

Oxygen is a scarce commodity in the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis. Bacteria growing at a colony’s outer edges may have access to oxygen, but bacteria buried under their siblings would suffocate without a way to gain oxygen. Phenazines act like molecular snorkels giving bacteria that are crowded or submerged in mucus access to fresh air, Dietrich says.

Colonies of P. aeruginosa that make phenazines grow in petri dishes as smooth, shiny colonies. But bacteria that lack the molecules form wrinkled colonies. Dietrich thinks the wrinkles probably increase surface area to bring more bacteria in contact with oxygen.

The idea that bacteria can use phenazines to access essential nutrients, such as oxygen, is “exciting,” says Linda Thomashow, a research geneticist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service in Pullman, Wash. The result fits with her research, which shows that phenazines give bacteria a competitive advantage in soil.