Wild birds, especially ducks and geese, like these flying by a farm in Illinois, can spread H5N1 bird flu to poultry. Keeping the wild and domestic birds separate is a challenge.

John Ruberry/Getty Images

H5N1 bird flu isn’t going away. In fact, the virus continues to spin off new versions that outcompete their predecessors, posing a challenge for keeping it from jumping into people, poultry and other animals.

“These viruses are becoming more fit, in the sense that we’re seeing more progeny viruses … [and] that these viruses seem to be spreading more broadly as they evolve,” says Anthony Signore, an evolutionary biologist at the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s National Centre for Foreign Animal Diseases in Winnipeg.

Signore and colleagues examined DNA from 2,955 bird flu viruses. The results, reported July 9 in Science Advances, map how H5N1 viruses exchanged genetic material with other avian influenza strains and spread through North and South America. And H5N1 bird flu virus will probably continue to swap parts with other viruses and acquire mutations that allow it to better replicate in birds and possibly other species.

At some point, virus spread may plateau, but that hasn’t happened yet, Signore says. These viruses “come and go with bird migration, and [there] doesn’t seem to be any end in sight.”

These particular H5N1 viruses already are “beyond comparison to the others in terms of [their] ability to impact and infect different species,” says Erin Sorrell, a global health security expert at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Versions of H5N1 have infected an array of birds, mostly wild waterfowl and domestic poultry, as well as a huge variety of mammals, including dairy cattle, cats, a pig and humans. In the United States, 70 people are confirmed to have been infected and one died. But some studies suggest more people may have been infected than official reports count.

The H5N1 bird flu viruses now spreading are highly pathogenic to poultry and can kill a chicken or turkey within 24 to 48 hours, Sorrell says. Since the start of the outbreak in 2022, nearly 175 million birds in the United States have either died from infection or been culled from commercial and backyard poultry flocks.

Protecting flocks from H5N1

How to keep poultry flocks, dairy herds and people safe from the increasingly prolific bird flu viruses may be an insurmountable hurdle. Scientists and government officials are contemplating many approaches including vaccinating poultry. U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has suggested letting bird flu rip through poultry flocks; surviving birds would have some genetic immunity and so could be used to repopulate flocks, he argues. But that approach is unlikely to work and could lead to even more devastating consequences, Sorrell and colleagues cautioned in the July 3 Science.

On the move

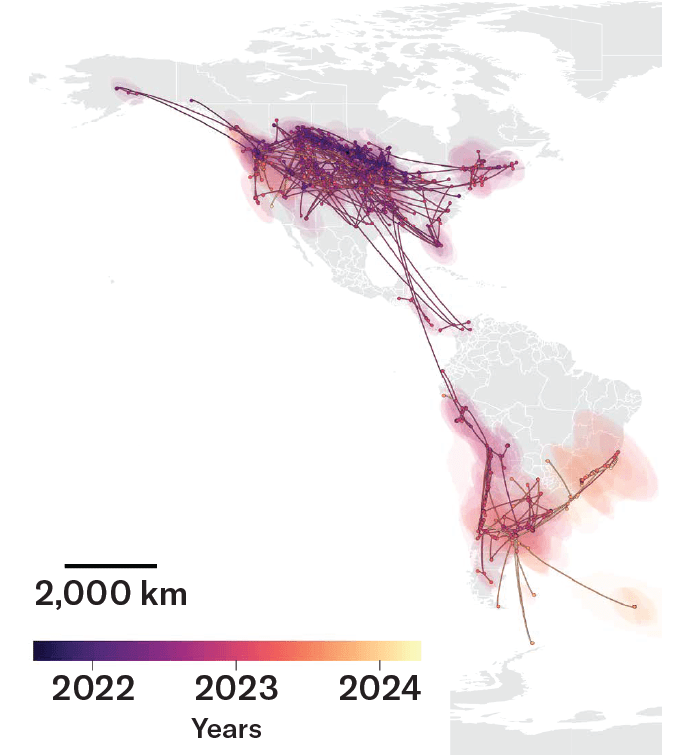

Wild birds, especially waterfowl, carried H5N1 bird flu variants throughout the Americas. This map shows distribution of a variant called B3.2, which outcompeted earlier variants in the spring of 2022 and was replaced by a fitter variant in the fall of 2023. Crows, ravens, bluejays and magpies may have played a role in the early spread of B3.2. Each line represents transmission from one site to another and is curved counterclockwise to indicate the direction of spread.

Commercial poultry are bred to be nearly genetically identical and few if any birds survive an H5N1 infection, Sorrell says. If the virus spreads unchecked, not only would there be too few birds to repopulate the broiler and breeder flocks, the ones that survive may not have the genetic chops to sustain egg or meat production.

Any surviving birds probably wouldn’t have a genetic advantage over the virus, Sorrell says. Their survival would more likely depend on preexisting immunity from a prior infection with another type of bird flu. Such immunity might keep a bird from dying of H5N1 but could allow it to be a vessel for further H5N1 replication. That’s also a worry for vaccinations that limit disease but don’t prevent infection.

“Letting the virus spread is the same as letting it evolve,” says Anice Lowen, a virologist at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta who was not involved with either study. The concern is that the virus could adapt to better infect hosts, including humans. Recombination of H5N1 with viruses that cause seasonal flu in people or with swine flu viruses could lead to a pandemic strain, Lowen says.

Keeping wild and farm birds apart

The best strategy may be to prevent H5N1 from spilling over from wild birds into poultry flocks and dairy herds. Doing that may require thinking outside the barn, says Maurice Pitesky, a veterinarian and epidemiologist at the University of California, Davis. “If we just focus on the barn, we’re already ceding all that habitat that surrounds our facility to the waterfowl and putting a barn in an almost impossible situation when it comes to biosecurity.”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture said it will deploy 20 epidemiologists to conduct free biosecurity audits and wildlife assessments at poultry farms. The effort is inadequate, Pitesky says. Not only are there not enough epidemiologists to survey the more than 270,000 U.S. poultry farms, but the audits stop at the perimeter of the farm and don’t consider habitat nearby where infected waterfowl may roost. Nor do the epidemiologists warn farmers when migrating birds pose an additional risk, he says. “At the minimum, it’s incomplete.”

Pitesky is among researchers tracking movements of wild birds and linking their presence to H5N1 outbreaks. He advocates strategically flooding wetlands to attract ducks and geese, which are the major spreaders of the virus, to areas away from poultry and dairy farms. Water cannons, lasers, noise and other measures can also discourage waterfowl from landing near farms.

Right now, outbreaks of H5N1 are declining because waterfowl are in the Arctic where they nest and breed in the summer. But this slow time is exactly when governments and farmers should be gearing up for when the birds return in the fall carrying new and potentially scarier versions of the virus that evolved in the summer breeding grounds, Pitesky says.

Sorrell says that state and local veterinarians and epidemiologists need resources and staffing to prepare for the fall migration. Preventative measures can be a hard sell, though, she says. “If you’ve prevented an outbreak, you can’t really prove it, so it’s hard to show your return on investment.” Even with the best preparation, the virus probably has surprises in store, she says. “This H5 virus has taught us that these viruses are always one step ahead of us.”