Brain speed-reads using just one part

Broca’s area involved in both reading and speaking words

The brain goes from zero to speech in 600 milliseconds. Scientists have known this fact, but have debated exactly how the brain processes language and then converts the thoughts to speech.

Questions have centered on the role of Broca’s area, a language-processing center located on the left side of the brain and first described by the French doctor Pierre Paul Broca in 1865. Since then, researchers have made little progress in understanding the details of how the area helps a person speak, partly because tools such as functional MRI are too slow to measure the activity of single neurons or groups of neurons.

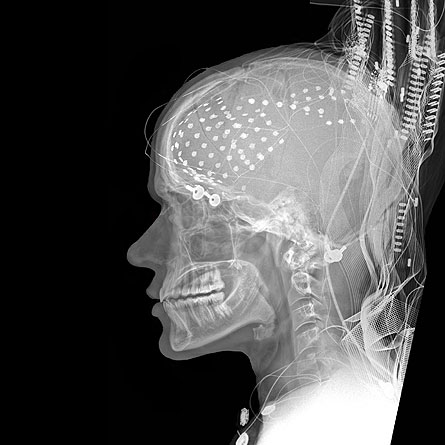

Now, patients with epilepsy are giving researchers split-second insight into language processing in Broca’s area. Three people with epilepsy had a rare surgery to implant electrodes in their brains. The surgery allows doctors to pinpoint the source of seizures and treat the condition while sparing parts of the brain that control language, vision and other important processes. The patients gave permission for Ned Sahin of the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and his colleagues to measure activity in their brains during pre-surgery tests.

Those measurements showed that Broca’s area is able to do more than scientists had thought, including executing all steps from reading to speaking. The area recognizes words within 200 milliseconds of a person seeing them. Then it takes only another 120 milliseconds to mentally change the tense of a verb or make a noun singular or plural. By 450 milliseconds after first seeing a word, the brain is ready to silently articulate it.

These findings may help dispel a commonly taught notion that Broca’s area is only involved in speaking while a different part of the brain, known as Wernicke’s area, handles reading and hearing, Sahin says. The study appears in the October 16 Science.