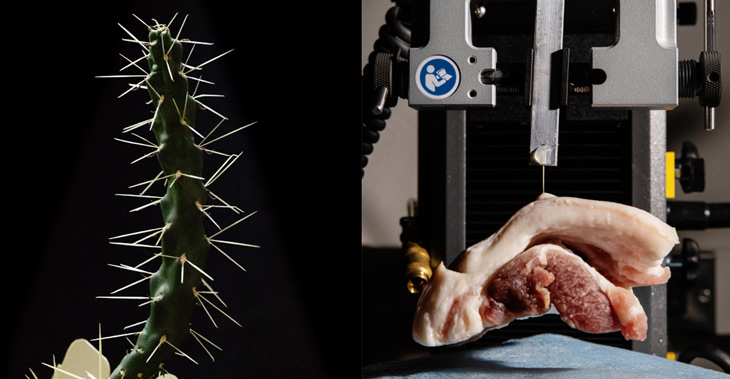

Cactus spine shapes determine how they stab victims

Tests in hunks of meat revealed that some spines simply poke, while others hitch a ride

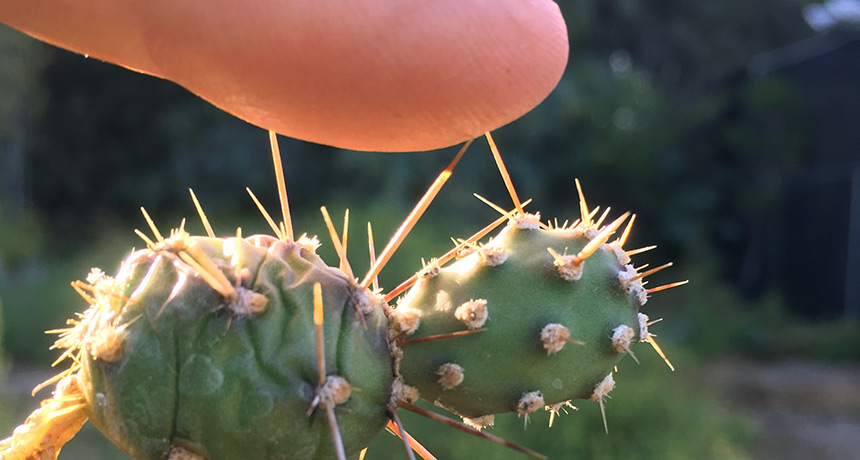

THE SPINE WHO LOVED ME Scientists are working to understand how cactus spines, like those from this brittle prickly-pear cactus (Opuntia fragilis), puncture their victims so easily.

John Trager