Genetically engineered immune cells have kept two people cancer-free for a decade

Doctors say long-lasting effects show CAR-T therapy can ‘cure’ some patients

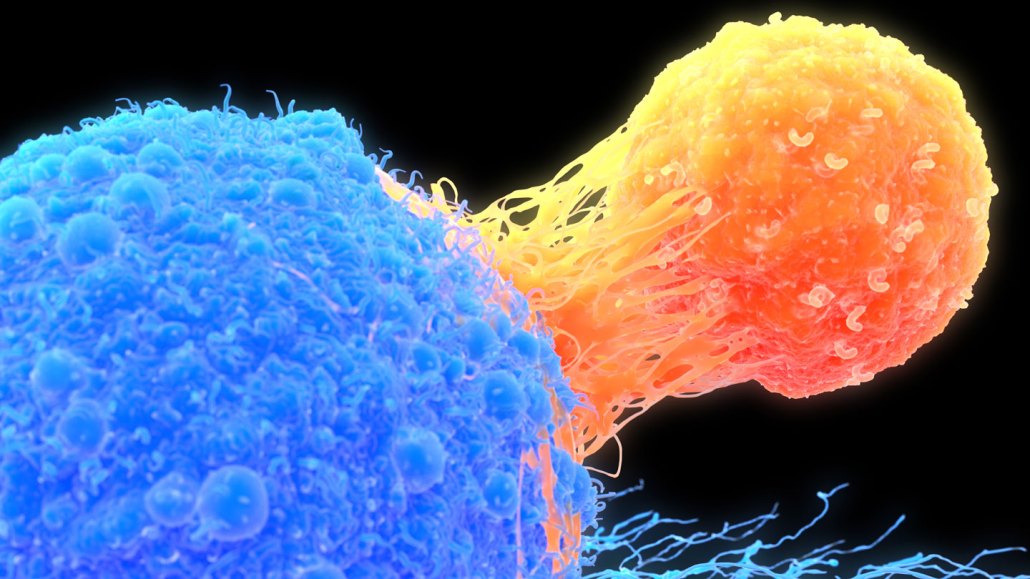

A decade after two blood cancer patients received a novel type of immunotherapy involving immune cells called T-cells that had been genetically engineered, the cells are still in the people’s bodies and their cancer is still in remission. A T-cell (orange) is shown attacking a cancer cell (blue) in this illustration.

Roger Harris/Science Photo Library/Getty Images Plus