The coronavirus cuts cells’ hairlike cilia, which may help it invade the lungs

Trimming the structures prevents mucus from moving the invaders out toward the throat

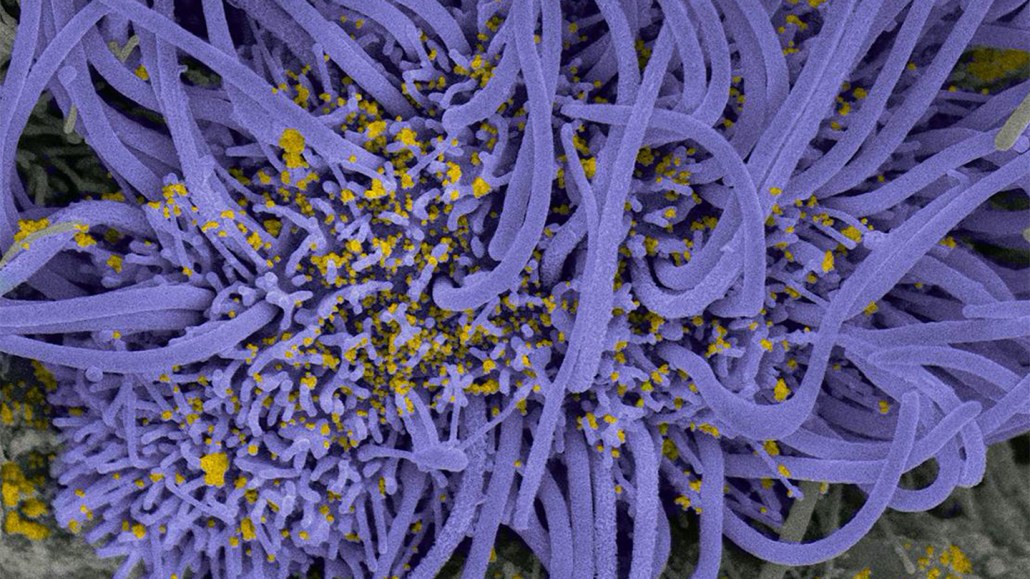

When the coronavirus infects cells in the respiratory tract, it can truncate hairlike projections called cilia, as seen in this artificially colored scanning electron micrograph. (Viral particles are shown in yellow.) That can make it harder for the lungs to clear pathogens.

Vincent Michel, Rémy Robinot, Mathieu Hubert, Olivier Schwartz and Lisa Chakrabarti/Institut Pasteur