Preventing dangerous blood clots from COVID-19 is proving tricky

Anti-clotting medicines may help stem excessive blood clotting, but the best dose isn’t clear

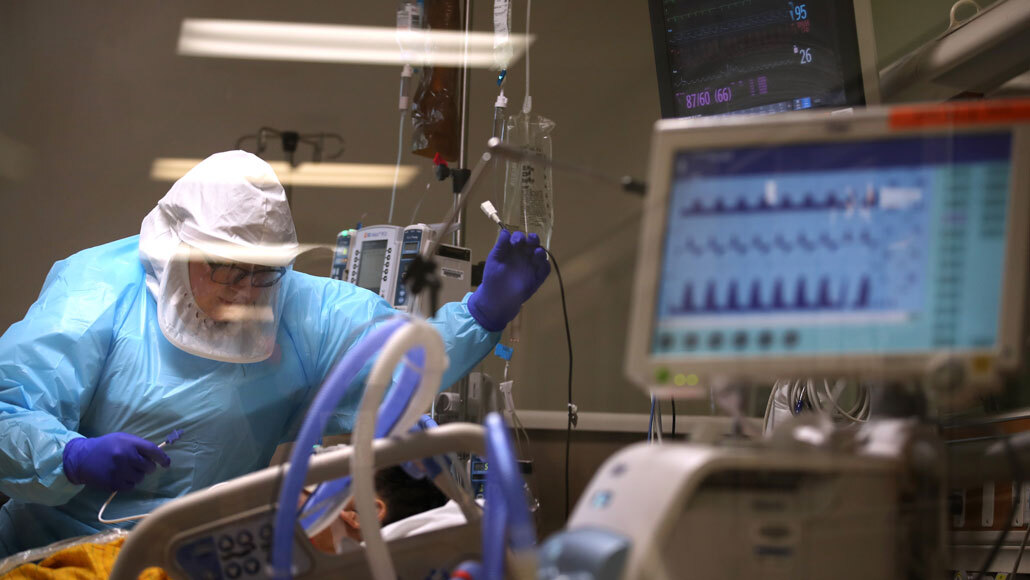

A nurse cares for a critically ill COVID-19 patient at Regional Medical Center in San Jose, Calif., on May 21. Extensive blood clotting can be a complication of serious coronavirus infections and clinical trials to investigate treatments have begun.

Justin Sullivan/Staff/Getty Images News

For some severely ill COVID-19 patients, the struggle to take in enough air is not only due to having fluid-clogged lungs. The quest for oxygen also is stymied by a plethora of blood clots.

As it’s become clear that excessive clotting can be a complication of a serious coronavirus infection, there’s been debate over how best to manage the blockages. Now clinical trials are under way to assess different doses of anticoagulants, medicines already used to prevent or break up blood clots in other patients. But it’s not as easy as “the more, the better” since, in general, higher doses come with higher risks of major bleeding.

Striking the right balance between clotting and bleeding is something the body itself does regularly, and not just after an injury. Infections spur clotting too. That’s because the immune system, inflammation and clotting are linked.

If the regulation of these systems gets out of whack, the scales can tilt toward thromboinflammation, in which severe inflammation leads to excessive clotting. For COVID-19 patients, that’s happening to an alarming degree. But the dose of anticoagulant used to prevent blood clots in other patients, at risk after surgery or other procedures, is not working for coronavirus-related clotting. Figuring out if there is an effective dose and the best time to treat could be one part of helping COVID-19 patients.

Why clotting can be a complication of a serious infection is rooted in its role in the immune system. Although well known for stopping catastrophic bleeding at the site of a cut, there’s more to clotting than just plugging leaks. Clots can also trap pathogens, preventing them from invading tissues and traveling throughout the body.

When the innate immune system — the body’s first defense against pathogens — becomes alert to an invader (SN: 4/23/20), the body begins releasing proteins that ramp up inflammation, and certain immune cells activate the clotting system. Pathogens get trapped in a clot like a fly in a spider web, held fast until immune cells come in for the kill.

But for some COVID-19 patients, the clotting response becomes excessive, putting their lives at risk when blood vessels become blocked. Pulmonary embolisms, which happen when a clot breaks free from a vein and gets stuck in the lungs, are common in these patients. The clots are also happening at the level of the smallest blood vessels, which disrupts the delivery of oxygen, damaging organs.

“It’s the people who get really sick who seem to have the worst problem with developing blood clots,” says clinical hematologist Jean Connors of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Some of these patients “have such a dramatic immune response” and heightened inflammation, which in turn leads to severe clotting, she says.

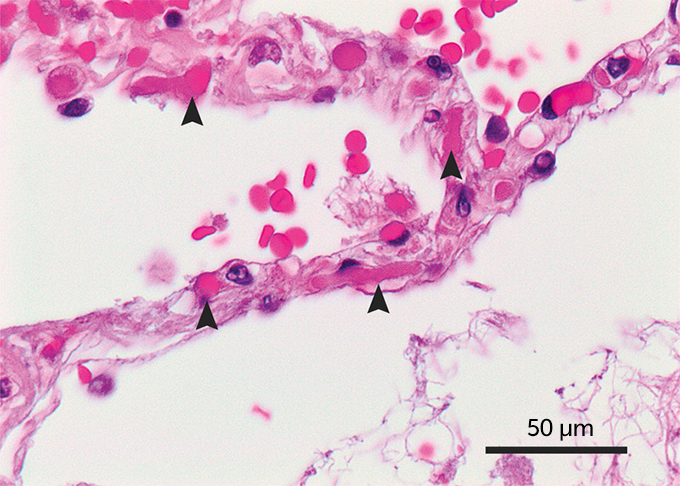

And the clotting appears to be worse than that experienced by patients with different diseases but a similar severity of illness. A small autopsy study that compared the lungs of patients who died from either COVID-19 or from influenza A (H1N1) in 2009 suggests that clots were a bigger problem with the coronavirus. Clotting in the tiny blood vessels associated with the alveoli, the little air sacs that allow the exchange of oxygen between the lungs and the blood, was widespread in the lungs of seven COVID-19 patients compared with the lungs of seven influenza patients, researchers reported May 21 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The lungs of COVID-19 patients in the autopsy study also revealed gravely injured endothelial cells, which line blood vessels. These cells normally keep clots at bay so that blood can flow smoothly. But “the virus seems to cause damage to the lining of the blood vessel,” says hematologist Maria DeSancho of Weill Cornell Medical College. When damaged, the cells activate clotting.

Other parts of the body’s response to COVID-19 may be stoking clotting as well, each adding to the excess. “It’s a vicious cycle,” DeSancho says.

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.

When extensive clotting happens in COVID-19 patients, it increases the chance they’ll die. A study of 184 patients admitted to the intensive care units of three hospitals in the Netherlands found that 75 had thromboses, clots that partially or completely block vessels; of those, 65 were pulmonary embolisms. As of April 22, 41 of the patients had died. The patients diagnosed with thromboses had a much higher risk of death than those without thromboses, researchers report in the July issue of Thrombosis Research.

Although medicines are widely available to treat and prevent blood clots, the question is whether there’s a dose that will work for the dramatic amount of COVID-19 clotting. Trials in the United States, Canada and Europe have begun recruiting patients to find the answer, with more trials in the planning stages.

One trial, called RAPID COVID COAG, is enrolling hospitalized patients with confirmed COVID-19 and with blood tests showing an elevated level of a substance called D-dimer, a by-product of blood clotting. (D-dimer can mean that a person has had a blood clot, or that the body is inflamed and at risk of a clot.)

Participants will be randomly split into two groups. One will receive a low dose of an anticoagulant, one normally used to prevent a clot from forming in a person at risk due to surgery, for example. The other group will get a high dose, an amount normally used to break up a diagnosed blood clot.

“The idea behind our trial is to initiate anticoagulation at a higher dose earlier on to determine whether or not that’s effective at decreasing the risk” of worsening illness or death, says hematologist Michelle Sholzberg of the University of Toronto and St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto. The trial should wrap up by the end of the year.

Though it’s not surprising that severe inflammation can increase the risk of clotting, the “predisposition to clots or full-blown clotting” seen in COVID-19 appears distinct, Sholzberg says. “This is … a level of thromboinflammation that we have not really witnessed before on such a large scale.”