Eastern Polynesia’s settlers rapidly voyaged across a vast area starting nearly 1,200 years ago, a new genetic study finds. Groups with a shared ancestry may have carved massive statues on easternmost islands, including these on Easter Island.

Atlantide Phototravel/Getty Images Plus

Polynesian voyagers settled islands across a vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean within about 500 years, leaving a genetic trail of the routes that the travelers took, scientists say.

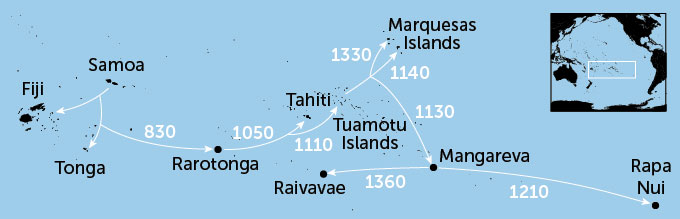

Comparisons of present-day Polynesians’ DNA indicate that sea journeys launched from Samoa in western Polynesia headed south and then east, reaching Rarotonga in the Cook Islands by around the year 830. From the mid-1100s to the mid-1300s, people who had traveled farther east to a string of small islands called the Tuamotus fanned out to settle Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, and several other islands separated by thousands of kilometers on Polynesia’s eastern edge. On each of those islands, the Tuamotu travelers built massive stone statues like the ones Easter Island is famed for.

That’s the scenario sketched out in a new study in the Sept. 23 Nature by Stanford University computational biologist Alexander Ioannidis, population geneticist Andrés Moreno-Estrada of the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity in Irapuato, Mexico, and their colleagues.

The new analysis generally aligns with archaeological estimates of human migrations across eastern Polynesia from roughly 900 to 1250. And the study offers an unprecedented look at settlement pathways that zigged and zagged over a distance of more than 5,000 kilometers, the researchers say.

“The colonization of eastern Polynesia was a remarkable event in which a vast area, some one-third of the planet, became inhabited by humans in … a relatively short period of time,” says archaeologist Carl Lipo of Binghamton University in New York, who wasn’t involved in the new research.

Improved radiocarbon dating techniques applied to remains of short-lived plant species unearthed at archaeological sites are also producing a chronology of Polynesian colonization close to that proposed in the genetic study, Lipo says.

In the new investigation, researchers identified DNA segments of exclusively Polynesian origin in 430 present-day individuals from 21 Pacific island populations. Island-specific genetic fingerprints enabled the scientists to reconstruct settlement paths, based on increases in rare gene variants that must have resulted from a small group moving from one island to another and giving rise to a new, larger population with novel DNA twists. Comparisons of shared Polynesian ancestry between pairs of individuals on different islands were used to estimate when settlements occurred.

In an intriguing twist, the DNA evidence “is consistent with the [statue] carving tradition arising once in a single point of common origin, likely the Tuamotu islands,” Moreno-Estrada says. Polynesian ancestry on all the islands with massive statues traces back to the one island in the Tuamotus where the researchers were able to obtain Indigenous peoples’ DNA.

The Tuamotus include nearly 80 islands situated between Tahiti to the west and other islands to the north and east where settlers carved statues. The latter outposts consist of the Marquesas Islands, Mangareva and Rapa Nui. Another late-settled island where inhabitants carved statues, Raivavae, lies southwest of the Tuamotus.

Settlers reached the island of Mataiva in the northern Tuamotus by about 1110, the researchers suggest. Statue makers navigated northward and eastward from Mataiva or perhaps other Tuamotu islands to as far east as Rapa Nui — eventually curving back west before arriving at Raivavae — around the same time as an earlier DNA study suggests eastern Polynesians mated with South Americans (SN: 7/8/20). (It’s not clear whether South Americans crossed the ocean to Polynesia or Polynesians traveled to South America and then returned.)

Pacific trek

Caption: An analysis of 430 present-day individuals is shedding new light on the timings and routes of early Polynesians’ migrations. Modern DNA indicates that voyagers left Samoa and went south and then east, reaching Rarotonga in the Cook Islands by around the year 830. From the mid-1100s to the mid-1300s, people who had traveled to the Tuamotu Islands, located just east of Tahiti, spread out to settle Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, and several other islands separated by thousands of kilometers.

When early Polynesians migrated eastward

Ioannidis and colleagues’ conclusions generally support prior scenarios of Polynesia’s settlement, but some disparities exist between their genetic evidence and earlier archaeological and linguistic findings, writes archaeologist Patrick Kirch of the University of Hawaii at Manoa in a commentary published with the new study.

For instance, the new DNA analysis overlooks extensive contacts that occurred across eastern Polynesian in its early settlement stages, Kirch says. Analyses of closely related eastern Polynesian language dialects and discoveries of stone tools that were transported from one island to another point to substantial travels and trading throughout the region during that time.

Kirch, who has previously suggested that these long-distance contacts in eastern Polynesian influenced stone carving traditions, calls the new proposal that people with a shared ancestry brought stone carving to Rapa Nui and other islands “a provocative hypothesis.”

And there’s still no answer to one major question regarding the settlement of the islands, says molecular anthropologist Lisa Matisoo-Smith of the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, who didn’t participate in the new research. No current line of evidence can resolve the mystery of why, after spending nearly 2,000 years on Samoa, Tonga and Fiji, Polynesians began voyaging thousands of kilometers eastward in search of new lands.