Emissions of a banned ozone-destroying chemical have been traced to China

Air monitoring data solve only part of the mystery of why CFC-11 pollution is on the rise

POLLUTION PATROL Air samples collected at stations in Gosan, South Korea (above) and Hateruma, Japan indicate that eastern China has been ramping up its emissions of an outlawed chemical called CFC-11.

Korean Meteorological Administration

China has continued producing an ozone-destroying chemical called CFC-11 in violation of an international agreement, an analysis of atmospheric gas finds.

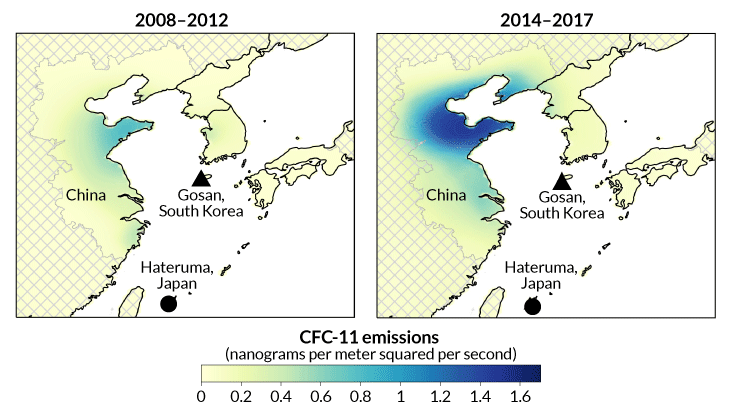

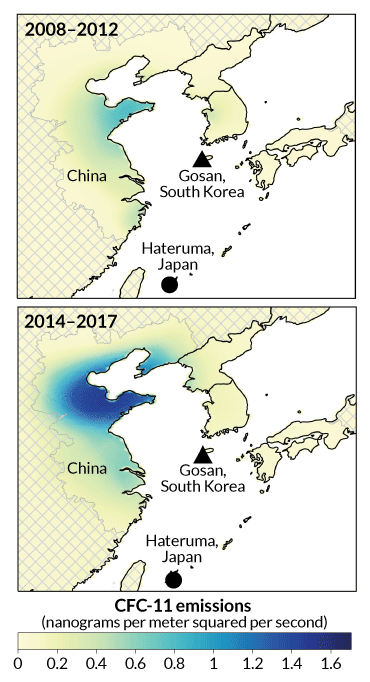

Air samples collected in South Korea and Japan suggest that eastern China emitted around 7,000 metric tons more trichlorofluoromethane a year from 2014 to 2017 than it did from 2008 to 2012. This boost in emissions explains a large fraction of the estimated global increase in CFC-11 emissions — between 11,000 and 17,000 metric tons annually — after 2012, researchers report online May 22 in Nature.

CFC-11 has been used to make foams for construction materials, refrigerators and consumer products. But chlorine from CFC-11 and similar molecules, collectively called chlorofluorocarbons, can destroy thousands of atmospheric ozone molecules per chlorine atom (SN: 12/1/12, p. 13). Under the 1987 Montreal Protocol, an international treaty that phased out the production of chlorofluorocarbons by 2010, no one should be producing CFC-11 anymore (SN: 7/7/90, p. 6).

“Now there is a very clear indication that some places are not adhering to the Montreal Protocol,” says A.R. Ravi Ravishankara, an atmospheric scientist at Colorado State University in Fort Collins not involved in the work.

These results demonstrate “the need for verification and continued vigilance” in enforcing the treaty, he says. Continuing illegal production of the chemical may delay the recovery of the hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica.

Initial hints of illegal CFC-11 production came last year when atmospheric observations revealed that the global decline of CFC-11 slowed significantly after 2012. These results were reported in Nature in May of 2018, but the culprits responsible for ramping up CFC-11 emissions remained a mystery. The data indicated only that some of the emissions might hail from eastern Asia.

Sunyoung Park, a geochemist at Kyungpook National University in Daegu, South Korea, and colleagues homed in on the CFC-11 source by analyzing air samples collected from 2008 to 2017 at atmospheric monitoring sites around the world. This network included stations in eastern Asia, Europe, North America and Australia.

“In the non-Asian stations, the signals are consistent with declining regional emissions, whereas at the eastern Asian stations, we saw signals that very strongly suggested that emissions increased,” says Matthew Rigby, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Bristol in England. Stations in Hateruma, Japan and Gosan, South Korea showed spikes in CFC-11 concentration as plumes of pollution wafted overhead. Those spikes grew after 2012.

CFC-11 spike

Atmospheric observations from Gosan, South Korea and Hateruma, Japan suggest that annual CFC-11 emissions in eastern China increased by about 7,000 metric tons between 2008–2012 (left) and 2014–2017 (right). This accounts for about 40 to 60 percent of the estimated recent increase in global CFC-11 emissions.

Emissions of a banned chlorofluorocarbon in eastern Asia, 2008–2012 and 2014–2017

The team ran computer simulations of the atmosphere to determine where the CFC-11 could have originated. The simulations indicated that from 2008 to 2012, eastern China emitted an average of about 6,400 metric tons of CFC-11 per year. That number increased to about 13,400 metric tons per year from 2014 to 2017. This boost in pollution arose primarily around the northeastern Chinese provinces of Shandong and Hebei. The researchers found no evidence of significantly increasing emissions from any other eastern Asian countries.

On-the-ground investigations undertaken by the international Environmental Investigation Agency, or EIA, and Chinese authorities have similarly turned up evidence of illegal CFC-11 use in manufacturing. “China will continue cracking down on illegal production and use of [ozone depleting substances] and strengthen regulation over relevant industries,” Zeng Rong, a spokesperson from the Chinese Embassy in England, wrote in a letter to the Guardian in August 2018 in response to a news article about China’s production of CFC-11.

The new study’s finding “leaves behind a few very important questions,” Ravishankara says. For one thing, the annual 7,000-metric-ton bump in CFC-11 emissions from eastern China accounts for only about 40 to 60 percent of the estimated global increase in CFC-11 emissions after 2012. That leaves atmospheric scientists to wonder where the rest is from. “It really would help if [we had] these measurements from other parts of the world,” he says. The network of monitoring stations used in this study doesn’t extend to other parts of Asia, Africa or South America.

Further investigations are also necessary to tease out which industrial processes are responsible for the emissions, Rigby says. If CFC-11 gas is trapped inside newly manufactured materials like foams, that gas will eventually leak into the atmosphere. “It’s entirely possible that the total emissions that we’ve seen so far are actually a relatively small fraction of the total amount of CFC-11 that was produced,” he says.

The overall amount of CFC-11 pumped into the atmosphere will determine its effect on the ozone layer, which protects life on Earth from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. The hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica has been shrinking (SN: 12/24/16, p. 28), and is expected to close between 2060 and 2070, says James Elkins, an atmospheric scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Boulder, Colo. Elkins was involved in the 2018 study that first flagged increasing CFC-11 emissions.

“If we immediately stopped those increased emissions, then it [may] not affect much,” Park says, but if emissions keep increasing, “the ozone recovery we’re expecting could be significantly delayed.”