Engineered vocal cords show promise in animal tests

Lab-grown tissue could treat people who have lost voice to surgery, disease

HARMONY Vocal cord tissue grown in the lab vibrates just like tissue in a healthy larynx (illustrated here), a promising sign for people with voice problems.

Sebastian Kaulitzki/Shutterstock

Vibrating tissue that hums in tune with normal, human vocal cords has been grown in a lab for the first time.

The bioengineered tissue opens a route to developing new therapies for people who have lost their voice due to surgery or disease. The tissue was tested in dog cadaver organs that house the vocal cords and in mice with humanlike immune systems, University of Wisconsin–Madison researchers report in the Nov. 18 Science Translational Medicine. Not only did the mice accept the lab-grown vocal folds, but the tissue trumpeted a healthy vibrato in the dogs’ larynges, too.

“It was really indistinguishable from normal vocal fold vibration,” says study coauthor Nathan Welham, a speech language pathologist at Wisconsin’s School of Medicine and Public Health.

Around 30 percent of Americans have experienced a voice-related issue during their lifetimes, Welham says. In the most serious cases — such as laryngeal cancer — large swaths of vocal cord tissue might be removed surgically. Without the tissue, people are left unable to speak, diminishing a person’s quality of life, says Seth Cohen, a laryngologist at the Duke University School of Medicine in Durham.

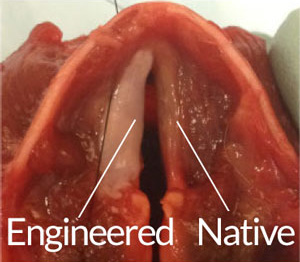

Dogs, like humans, have two vocal folds. A lab-grown fold was grafted next to a fold in a dog larynx. By blowing hot, humid air across the tissue, the researchers found that both the lab and dog folds produced a similar sound and vibration rate of roughly 180 times every second.

Vocal cord tissue was then inserted in mice that had immune systems similar to humans. One group of mice had blood and larynx tissue cells that came from different people. Another mouse bunch received samples made from a single person. In both cases, the mice didn’t reject the engineered tissue, a sign that the tissue might work in the human body, too.

While Welham says this approach can make healthy vocal cord tissue that can restore normal voice function, he notes that a number of clinical and approval steps are still needed before the tissue can be used in humans.

But because the vocal fold tissue is so specialized and difficult to replicate using other materials, Cohen says that the study is a step in “moving toward being able to help people where we don’t have a good treatment.”

Editor’s Note: This story was updated December 7, 2015, to correct the vibration rate of vocal cord tissue.