Epilepsy drug might harm fetuses

Children exposed to valproate in utero may face risk of lower IQs

Editor’s note: This story first appeared on SN Online April 15. Science News is reposting it as a way to communicate that, based on this study and other research, the American Association of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society decided on April 27 to recommend that women who have epilepsy avoid taking valproate during pregnancy.

“Good evidence shows that valproate is linked to an increased risk for fetal malformations and decreased thinking skills in children, whether used by itself or with other medications,” says Cynthia Harden, a physician at the University of Miami, a member of the American Academy of Neurology and one of the guideline authors.

The recommendations also counsel doctors to consider avoiding the epilepsy drugs phenytoin and phenobarbital for pregnant women, also to prevent the risk of cognitive damage to children.

Three-year-olds whose mothers took the drug valproate during pregnancy to control epilepsy seizures have lower IQ scores on average than children born to women who used other epilepsy medication, researchers report in the April 16 New England Journal of Medicine.

A pregnant woman with epilepsy faces a potentially terrible choice. Failing to control epileptic seizures places her fetus at risk, perhaps by limiting oxygen getting to the brain. But drugs that quell seizures also pose health risks to the fetus, including physical deformities and possibly cognitive losses.

Recently scientists have started to figure out which antiepileptic drugs might cause these problems. Some studies hint that valproate, marketed as Depakote, poses the greatest risk of physical and cognitive damage.

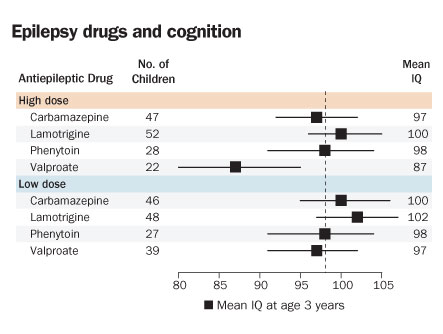

In the new study, researchers monitored the progress of 309 women from the start of a pregnancy to birth, and then measured IQs of the children at age 3. The children had been exposed to one of four antiepilepsy drugs in utero, at either high or low doses.

Children whose mothers had taken valproate while pregnant had IQs that were substantially lower on average than did children exposed to other antiepileptic drugs in utero. While the average IQ for the general population is 100, 3-year-olds whose mothers took valproate had an average IQ of 92. That is 9 points lower than those exposed to lamotrigine (Lamictal), 7 points lower than phenytoin (Phenytek or Dilantin) and 6 points lower than carbamazepine (Tegretol).

The scientists accounted for differences in the mothers’ IQs in doing the calculations.

Drug dose seemed to matter. Children whose mothers took high doses of valproate were significantly worse off (see chart), whereas lower doses weren’t associated with cognitive deficits in the offspring.

This study and previous research indicate that, for women in child-bearing years who have epilepsy and might get pregnant, valproate should not be a first-line drug choice, says study coauthor Kimford Meador, a neurologist at Emory University in Atlanta. Half of the pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, he notes, and a woman is often pregnant for a month or more before knowing it.

But it might not be as simple as that, Meador says. Valproate is the only drug that reliably controls seizures in one-sixth of patients with a kind of epilepsy called primary generalized epilepsy.

Women should consult their doctors before stopping or changing their medications, says neurologist Torbjörn Tomson of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. Doctors may need to manage seizures with a lower dose of valproate or find an effective replacement for the drug, he says.

In any case, this observational study might not be enough to change clinical practice, Meador says. The gold standard for such decisions is usually a trial in which people are randomly assigned to get one treatment or another. But giving pregnant women valproate in a trial would pose ethical questions, Tomson says.

“There are ongoing studies that will either confirm or refute the observations seen here,” he says.

Meanwhile, at least half of valproate prescriptions aren’t used for epilepsy at all. The drug, like other antiseizure medications, is often prescribed for bipolar disorder or migraines. Women taking it for these conditions should also be made aware of the risks, Meador says.