Evidence grows that an HPV screen beats a Pap test at preventing cancer

Switching to a human papillomavirus test may help reduce cases of the disease

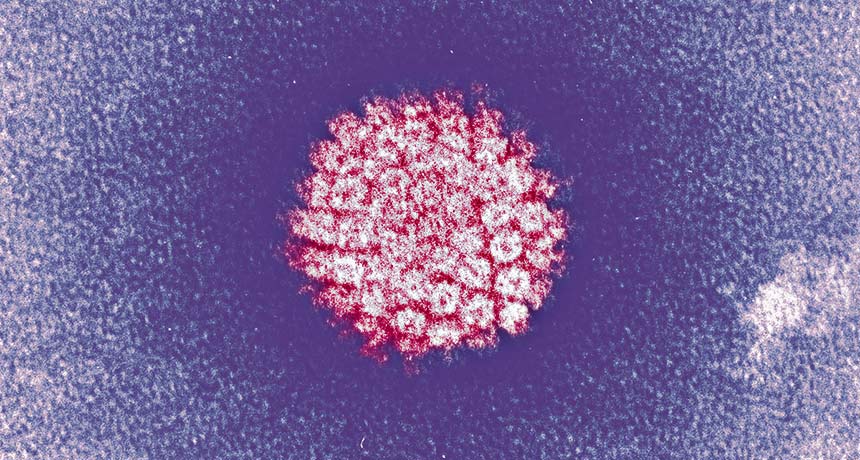

GUILTY AS CHARGED Human papillomavirus (shown) — especially types 16 and 18 —is responsible for nearly all cases of cervical cancer.

Laboratory of Tumor Virus Biology/NIH/Wikimedia Commons (adapted by E. Otwell)

Evidence continues to grow that screening for human papillomavirus infection bests a Pap test when it comes to catching early signs of cervical cancer.

In a large clinical trial of Canadian women, pap tests more often missed warning signs of abnormal cell growth in the cervix than did HPV tests, researchers report July 3 in JAMA. As a result, at the end of a four-year period, researchers found 5.5 new cases of severely abnormal, precancerous cervical cells per 1,000 women who got Pap tests, compared with 2.3 cases per 1,000 women who got HPV tests. Pap tests are the standard way to screen for cervical cancer.

“We should be moving away from screening with Pap tests toward screening with HPV tests,” says L. Stewart Massad, a gynecologic oncologist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, who wrote a commentary accompanying the study.

Previous research has found HPV testing leads to increased detection of abnormal cervical cells before they become cancerous compared with a Pap test. For instance, a 2009 study reported fewer cases of advanced cervical cancers and fewer deaths among women in India tested for HPV (SN: 4/25/09, p. 11). The study supported HPV testing in poorer countries, where cervical cancer screenings aren’t widespread. Worldwide, cervical cancer ranks fourth deadliest for women.

The new study suggests that HPV testing could also boost detection rates in countries that have well-established screening programs, such as the United States. Since the 1950s, the number of new U.S. cervical cancer cases and deaths has plummeted. The American Cancer Society estimates there will be 13,240 new cases, and 4,170 deaths, in 2018. The drop is primarily due to screening with the Pap test, in which cells are scraped from the cervix and examined for abnormal growth. But the test sometimes misses early signs of cancer.

An HPV test checks for the presence of a viral infection in cells swabbed from the cervix, similar to a Pap test. HPV, the most common sexually transmitted disease in the United States (SN Online: 4/28/17), causes nearly all cervical cancers. Following a positive result, doctors then examine the cervix for abnormal cells.

In the new study, roughly half of 16,000 Canadian women in an established screening program got the HPV test and the remainder a Pap test. After four years, all got both tests to check for missed cases. For the HPV-negative women, three more cases of abnormal cell growth were discovered after a Pap test. For women whose Pap test didn’t report abnormal cells, 25 additional cases were found after HPV testing.

“When [an] HPV [test] is negative, women are significantly less likely in four years to have anything abnormal,” says study coauthor Gina Ogilvie, a public health physician at BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre in Vancouver.

A switch to a screening system that starts with an HPV test will require education for patients and doctors. “Some women in their 40s and beyond in decades-long stable relationships may be alarmed to be identified with a new sexually transmitted infection,” which may have been contracted years before, Massad says. It will be important to emphasize that “the goal of cervical screening is to identify and remove HPV-infected cervical tissue from women at high risk.”