How attacks on evolution in classrooms have shifted over the last 100 years

Since the Scopes trial, Science News has reported on efforts to undermine the teaching of evolution

By Erin Wayman

Managing Editor, Print and Longform

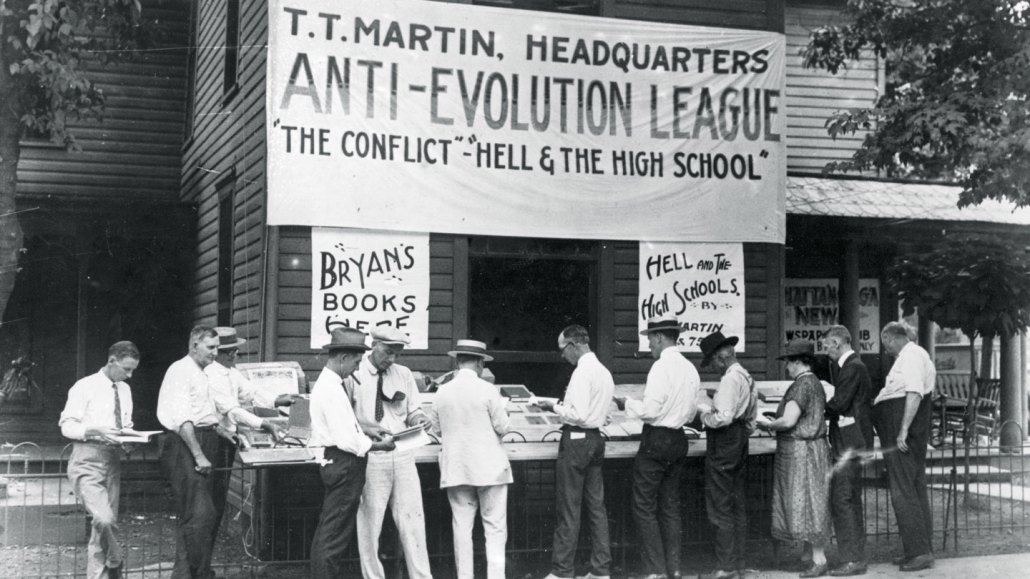

The 1925 Scopes trial brought publicity to the issue of teaching evolution, particularly human evolution, in the classroom.

Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

Reporters from across the United States flocked to eastern Tennessee in July 1925. In the small town of Dayton, biology teacher John Scopes went on trial for the crime of teaching human evolution. Among the journalists in the courtroom was Watson Davis, there on behalf of Science News-Letter, later rebranded as Science News.

One hundred years later, the Science News archive records the history of legislative attempts to undermine the teaching of evolution — the theory that unites biology — and how that effort evolved over time.

At the heart of the Scopes trial was a Tennessee state law that banned the teaching of human evolution. But by 1925, there was already fossil evidence that humans had indeed evolved from apelike ancestors. Neandertal fossils had been discovered in Germany in 1856, three years before Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species. The even more ancient species Homo erectus had been unearthed in Asia in 1891. And a skull that looked like a mash-up of an ape and a human had been uncovered in Africa in 1924. “There seems to be little doubt,” Science News-Letter said of the skull, “that there has been discovered … a most important step in the evolutionary history of man.”

When Davis and colleague Frank Thone, Science News-Letter’s biology editor, went to Dayton, they didn’t just report on the trial. They were also chummy with the defense lawyers, even staying in the defense team’s command post, which Thone called “the headquarters for the defenders of science, religion and freedom.” Davis also rounded up evolution experts who could testify on behalf of Scopes. Today, such activism is considered unethical in journalism. But standards were different in the 1920s. Even with Thone and Davis’ help, Scopes still lost.

Bans on teaching evolution prevailed for another 40 years, until high school teacher Susan Epperson took on Arkansas’ version. As Science News wryly noted, “Typically, Arkansas teachers skip [evolution] chapters or tell their students it is illegal to read them, thereby assuring that they will be read.” In 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the law as unconstitutional.

But that didn’t stop foes of evolution.

In the 1970s and ’80s, the aim became adding the “science” of creationism — the biblical belief that the universe and all life were created by God — to school curricula. In 1982, Science News covered a challenge to another Arkansas law, the Balanced Treatment for Creation-Science and Evolution-Science Act.

The American Civil Liberties Union had filed suit because creationism is not science, and the law “would bring religion into the schools,” Science News reported, noting that “the purpose of the law was to advance a religious belief.” A judge agreed and declared the law unconstitutional based on freedom of religion protected by the First Amendment.

In the 2000s, creationism returned to the classroom under a new guise, intelligent design. “That viewpoint holds, among other things, that organisms are too structurally and biochemically complex to have arisen only in accordance with natural forces,” Science News explained in 2006. The creator was left unsaid, but a federal judge still ruled that intelligent design was religion.

Today, several states have laws that define academic freedom as being able to teach scientific controversies, allowing the discussion of intelligent design and doubts about the theory of evolution. As we embark on our second century on the beat, Science News will continue to report on efforts to prevent the teaching of evolution.