100 years after the Scopes trial, science is still under attack

Teaching human evolution went on trial a century ago. What’s the case’s legacy?

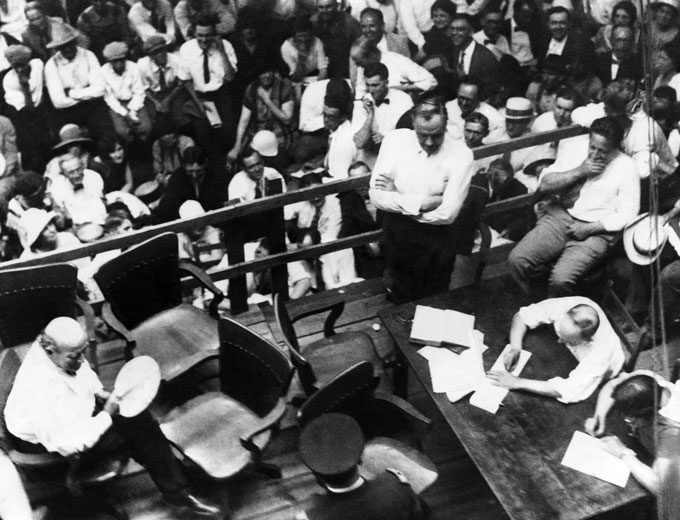

In July 1925, celebrity lawyers William Jennings Bryan (seated, left) and Clarence Darrow (standing, right) sparred over whether Tennessee could bar the teaching of human evolution.

Watson Davis/Smithsonian Institution

One hundred years ago, a small town in eastern Tennessee captured the attention of the entire country.

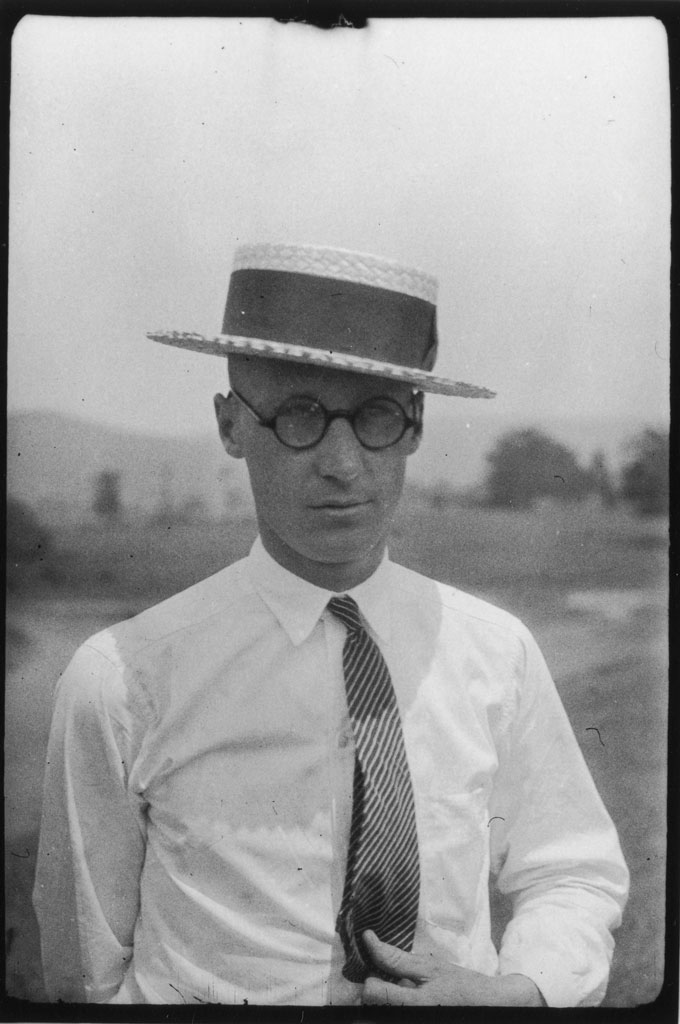

A biology teacher in Dayton was accused of teaching human evolution to his students — which was illegal in Tennessee at the time. The teacher went on trial for his crime, and it quickly became 1925’s biggest media event and one of the most sensationalized trials in U.S. history.

From July 10 to July 21, two nationally known, powerhouse lawyers — prosecutor William Jennings Bryan and defense attorney Clarence Darrow — traded barbs in acrimonious court proceedings that were about far more than one small-town teacher violating a state law. The trial was about religion versus science, old versus new and a personal beef between Bryan and Darrow that completely overshadowed John Scopes, the man ostensibly at the center of the case that still bears his name.

The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes, better remembered today as the Scopes trial, ended with Scopes being found guilty and fined $100, though the verdict was later overturned on a technicality. But the trial was not simply about Scopes’ innocence or guilt. It impacted science education for decades and teed up future court battles that far exceeded the Scopes trial in legal importance, though not in spectacle.

While the majority of Americans now accept the theory of evolution as valid, there remain those who reject the idea, even as it has become increasingly essential to understanding the natural world and humankind’s origins. Evolution also has broad practical implications for grasping the rise of new pathogens like the virus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic, the emergence of pesticide and antibiotic resistance, and how plants and animals adapt to changing environments.

Looking back on the famous trial, it’s impossible to ignore the parallels between the anti-evolution Christian fundamentalists of the Scopes era and today’s anti-science movements, including those that reject the reality of human-caused climate change or the safety of vaccines.

To commemorate the centennial of this part-trial, part–media circus, and to understand its legacy, freelance journalist Darren Incorvaia spoke with Randy Moore, a biologist at the University of Minnesota who has researched the Scopes trial for decades and penned the 2023 book John Thomas Scopes: A Biography. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

SN: The country was very different 100 years ago. What was life like back then and how did it set the stage for the Scopes trial?

Moore: The first cars were coming off assembly lines. Women claimed the right to vote in 1920. There was new music called the devil’s music: jazz. People were leaving rural areas and moving to cities. There was this great war — World War I — that shattered many people’s views of all this societal progress. Many people became afraid of change, and there was this collective nostalgia for the good old days.

Combined with that was a movement that came to be known as modernism. This new modern “religion” harmonized with Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Reason and logic became the arbiters of truth, not literal readings of scripture. Many people abandoned the old ways for this modernism, because they felt the old ways were narrow-minded, ill-suited for this new life. The modernists viewed traditional religion as a reversion to ignorance. Meanwhile, the traditionalists said, “This is how you destroy a country.”

SN: So there was a big reaction against this social change going on.

Moore: There was the advent and popularity of religious celebrities, preachers who tapped into this discontent and made opposing evolution their cause. Dwight Moody sort of started it in the 1800s in Chicago. Later, there was Billy Sunday, who would go into towns and attract 5,000 or 10,000 people per service.

Here in Minneapolis, about a mile from my office, was the guy who started to change everything. A preacher here at First Baptist Church named William Bell Riley realized that to change society, he had to get laws passed. He organized the World Christian Fundamentals Association in the late 1910s, and it caught on immediately. Riley was a Baptist, but the group was nondenominational and had membership of up to 6 million people at its height.

In 1925, Tennessee [state representative] John Butler introduced a law banning the teaching of human evolution, and it passed.

SN: Not all evolution, just human evolution?

Moore: Human evolution. That was the sacred cow. It’s fine for skunks to evolve.

Many politicians realized, how can we vote against the law? Billy Sunday had just been in Memphis. He had preached to almost 10 percent of Tennessee’s population. If they wanted to be re-elected, they couldn’t oppose it.

SN: So fundamentalists opposed human evolution because the idea that we share a common ancestor with other apes and evolved from earlier forms contradicts the Bible’s story of creation, a concern that anti-evolution groups still hold. But that wasn’t the only factor that led to the trial. The American Civil Liberties Union wanted to challenge the constitutionality of the law, and locals hoped a court challenge would bring publicity to Dayton. How did those forces combine?

Moore: A secretary at the ACLU saw a little news clipping about Tennessee criminalizing the teaching of human evolution and showed it to the executive director. They placed an advertisement in some Tennessee papers [seeking a defendant to challenge the Butler Act]. They got one response. An engineer named George Rappleyea was in Dayton to close a big coal plant. The coal industry had collapsed several years earlier. The population plummeted. The standard of living was down. They needed something to revive the economy. Rappleyea showed the ad to a group of local businessmen and said, “Why don’t we have a test case here?”

They weren’t activists in terms of evolution. But they realized, look at all this publicity. We can make some money. This could revive Dayton.

SN: How did they find their defendant?

Moore: They approached the high school’s full-time biology teacher, William Ferguson, who was also the school principal, and they asked him, “Would you consent to be arrested?” He said no. They came across John Scopes, who had been the substitute teacher in Ferguson’s biology class for two weeks in April of 1925. He was a first-year teacher and a football coach, and he immediately agreed to it. The trial could not have happened without his consent.

SN: How did the arrest of a small-town teacher charged with a misdemeanor evolve into a national event?

Moore: The next big step involved William Bell Riley, the guy in Minneapolis who organized the fundamentalists in opposition to evolution. Riley heard about this and said, “This is where we take our stand. Who can we get to represent us? William Jennings Bryan.”

Bryan was a national figure. He had run for president three times as the Democratic nominee [and was a former U.S. congressman and secretary of state]. He had been condemning evolution. And he said, “Yes, I will help prosecute John Scopes.”

His joining the prosecution was a big deal. And then the biggest publicity event occurred. Arguably the most famous criminal defense attorney in the country’s history, Clarence Darrow, volunteered to defend Scopes. Darrow had campaigned for Bryan. But Darrow hated Bryan’s turn to fundamentalism, especially his opposition to evolution. Darrow was an agnostic, and he wanted to expose Bryan’s fundamentalism.

When Darrow entered the contest, people immediately forgot about John Scopes. He was almost irrelevant in his own trial. It became Christianity versus atheism, the old versus the new, Bryan versus Darrow, a showdown. One day, they started the afternoon proceedings before Scopes even got to the courthouse. It wasn’t about him.

SN: What was this showdown like? How did the day-to-day of the trial go?

Moore: The prosecution claimed that just John Scopes is on trial. Did he teach human evolution? That’s the only issue. According to his own students, he did. Two of them got up and testified. Meanwhile, the defense explicitly said John Scopes isn’t on trial. The law is on trial. This is about his rights. Darrow brought in experts to testify about the validity of evolution, that evolution was a well-accepted idea. The prosecution objected. And on the second Friday of the trial, the 17th, the judge announced that expert testimony would be excluded, and most didn’t testify.

SN: What was the media coverage like? Was it as big as those businessmen hoped?

Moore: More than 100 reporters came to Dayton. Anything Scopes trial was selling papers. What Scopes wore. He was popular with the ladies. He was described as a great football coach. He was a media darling. They could not care less about evolution. They wanted the name-calling, and there was a lot of that. Reporters said, “My editor can’t get enough.”

The biggest event of the trial happened when the judge ruled that the scientific testimony was irrelevant. The weather had gotten so hot that the proceedings moved outside to this dais, and there was a crowd of several thousand people standing outside the Rhea County Courthouse watching the trial. The defense asked, “You would not let us put on experts about science, can we put on an expert about the Bible?” The judge said yes. And then the defense, in a spectacular move, called William Jennings Bryan as a witness. Bryan knew he couldn’t refuse. Darrow grilled him with questions about literal interpretations of the Bible. Was Jonah really swallowed by a big fish? Did the sun stand still? How old is the Earth?

Bryan defended himself relatively well, but the press portrayed him as the loser. Science News-Letter, the precursor of Science News, reported on “Bryan’s pitiful exhibition of ignorance.”

SN: That was a savvy move from Darrow. So in the eyes of the media, Darrow won the showdown with Bryan, even though Scopes lost the trial. What happened after the verdict?

Moore: One of the biggest impacts of the trial was that the word, literally the word, evolution disappeared from biology textbooks. Pictures of Charles Darwin were gone. It was a horrible loss for teaching evolution. This unifying idea in all of biology was not mentioned. Fundamentalism didn’t go away. It got stronger.

SN: And because Scopes’ conviction was overturned, the defense couldn’t appeal the case, right?

Moore: The ACLU looked for another defendant and couldn’t find one. And so the Butler Act was on the books for 40-something years, until the late 1960s.

Two other states had passed similar laws, Arkansas and Mississippi. A teacher challenged Arkansas’ law, and the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court ruled unanimously that banning the teaching of human evolution in public schools is unconstitutional [because it violated the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech].

SN: That’s Epperson v. Arkansas in 1968.

Moore: The plaintiff, Susan Epperson, was a new biology teacher in Little Rock. She felt she was in an untenable position. If I teach legitimate biology, I’m knowingly breaking the law. If I follow the law, I’m doing a disservice to my students. She was asked if she would test the anti- evolution law. After getting the enthusiastic support of her husband, she took on the case and won.

SN: But people don’t remember that trial, which seems like a big win for science and evolution.

Moore: There weren’t witnesses. There wasn’t an explosive Bryan versus Darrow confrontation. The lawyers stuck with the facts. You’re right; it was a dramatically important case for science education. The freedom for teachers to teach truth, to teach well-accepted ideas in public schools. Hard to top that one. Susan Epperson finished what John Scopes started.

SN: Today, anti-science sentiment can be found all across society, including in the federal government. What’s the legacy of the Scopes trial and how did it help get us to our current moment?

Moore: The Scopes trial is looked at as damaging the whole notion of expertise. The judge wouldn’t allow the scientific experts to testify, and we see that now with experts being shut down. Everybody has their own microphone now. Everyone’s an expert. And experts are important, but you need skepticism all the way through it.