Case-bearing leaf beetles get crap from their moms, and it’s a good thing they do.

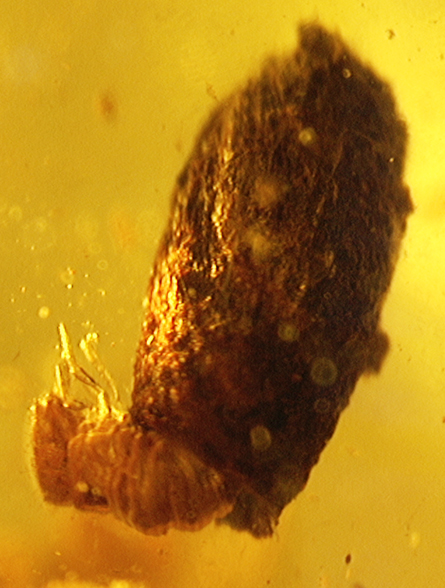

These beetles spend their youth wearing a growing cylinder of excrement that typically started as rows of rectangular plates that mom applied to the egg. Lab tests exposing young beetles to three kinds of predators show that the fecal architecture pays off in protection, says evolutionary ecologist Dan Funk of Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

One of the beetle species tested builds cases that have a junk-filled attic: a walled-off section at the top stuffed with white fuzz cut from the surfaces of sycamore leaves. That attic offers extra protection, Funk and Christopher G. Brown, of Shorter College in Rome, Ga., report. Youngsters with attics fared better when researchers let crickets choose to eat juveniles with or without attics on their cases, the researchers report in an upcoming Animal Behaviour.

This evidence for protection fits with an idea under study in leaf beetle evolution, says systematist Caroline Chaboo of the University of Kansas in Lawrence. Other leaf beetles have developed excremental structures, such as fecal parasols that bearers use to thump aggressors. So Chaboo is musing about whether advantages of the innovation promoted unusual diversity among fecal architects.

To see whether a fecal case itself deters predators, Brown and Funk collected two case-bearing species native to the southeastern United States: attic-builder Neochlamisus platani and Neochlamisus bimaculatus, which feeds on blackberry leaves.

House crickets, soldier bugs and lynx spiders all willingly ate larvae of both species that the researchers pried out of the cases. Attacking an encased larva proved less successful. Encased youngsters were more likely to live through the attack, the researchers report.

Youngsters get their first fecal protection from mom, who puts up to 45 minutes of effort into excreting and arranging the plates around a single egg. After the egg hatches, the larva keeps the original case but enlarges it daily and makes repairs. Only when beetles emerge from their pupal stage as flying adults do they abandon the fecal creation.

As excrement goes, the beetles produce remarkable stuff, Funk says. Despite weeks of wear, it stays firm and fungal-free. To a human nose it doesn’t smell and, after some complicated moments trying to collect larvae, Funk can add that it doesn’t have a discernible taste either.

Also, the fecal architecture permits the beetle to move around while grazing, notes Mike Hansell, emeritus professor of animal architecture at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. “It needs an armored car, not a castle — that imposes design constraints.”