Scientists perform the first pig-to-human lung transplant

The procedure could one day help address worldwide organ shortages

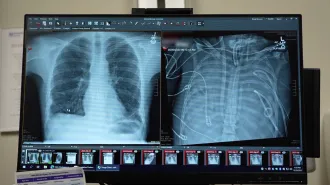

A genetically modified a pig lung transplanted into a human remained viable for nine days after the surgery, researchers report.

Halfpoint Images/Getty Images

Scientists have, for the first time, transplanted a genetically engineered pig lung into a human.

The lung tissue remained alive for nine days after the transplant despite early signs of inflammation, researchers report August 25 in Nature Medicine. The procedure was performed on a person who had been declared brain-dead, and it isn’t ready for clinical use yet. But it could help scientists understand and address the immune system’s response to a cross-species lung transplant.

Some scientists are investigating the process of transplanting organs between species, or xenotransplantation, as a potential solution to organ shortages worldwide. In the United States, 13 people die each day, on average, while waiting for an organ transplant. Surgeons transplanted a pig kidney into a human patient for the first time in 2021, and the first pig-to-human heart transplant occurred a few months later.

In the new study, researchers genetically modified a pig lung to reduce the chances that a human recipient’s body would reject the lung. Then, the team transplanted the lung into a 39-year-old man who had been declared clinically brain-dead after a brain hemorrhage.

The recipient’s body didn’t immediately reject the lung, the team found. But one day after the operation, the transplanted lung had partially filled with fluid and showed signs of inflammation. By day three post-operation, antibodies from the recipient’s immune system had begun to attack the lung.

Though the trial shows that lung xenotransplants into humans are possible, several limitations still prevent the widespread use of pig lungs for human patients, the scientists wrote in the study. For example, adding genetic modifications to the pig lung or refining the medicines that suppress the recipient’s immune response could help keep the transplanted lung alive and functioning longer.

It’s also not clear from the new study whether the transplanted lung could have supported the recipient without life support, says Richard Pierson III, a thoracic transplant surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston who was not involved with the research. Temporarily blocking blood flow to the remaining human lung shortly after the operation could have shown whether the transplanted lung was still functioning on its own and might have helped scientists understand the recipient’s early immune response, he says.

Because of these open questions, lung xenotransplants aren’t likely to become part of clinical practice in the near future, says Muhammad Mohiuddin, director of the Cardiac Xenotransplantation Program at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study. Mohiuddin’s team performed the first pig-to-human heart transplant in 2022. “It’s a learning process,” he says. “You will not see survival [times] in years very soon. The progress will be incremental.”