Newly discovered fossils provide the closest look yet at an anatomically quirky, 2 million-year-old member of the human evolutionary family. Discoverers of the ancient bones suspect they come from a species that served as an evolutionary bridge from relatively apelike ancestors to the Homo genus, which includes modern people.

Four papers published in the Sept. 9 Science describe a mosaic of humanlike and apelike skeletal traits on Australopithecus sediba, a recently proposed hominid species found at South Africa’s Malapa cave site (SN: 5/8/10, p. 14). Dates for newly exposed cave sediments, presented in a fifth paper in the same issue of Science, indicate that A. sediba lived there 1.977 million years ago, give or take several thousand years.

An international team led by anthropologist Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, views the new findings as consistent with its previous suggestion that A. sediba fossils at Malapa represent late-surviving members of a hominid line that gave rise to Homo.

That proposal is controversial. Some researchers doubt that A. sediba set the stage for the Homo genus. Others regard the Malapa fossils either as an early Homo species or as late-surviving members of Australopithecus africanus, a dead-end hominid species that lived from about 3 million to 2.4 million years ago in South Africa (SN: 5/7/11, p. 16).

“There’s still not enough evidence to place A. sediba squarely at the root of the Homo genus,” remarks anthropologist Brian Richmond of George Washington University in Washington, D.C. Several Homo fossils date to more than 2 million years ago, suggesting that A. sediba evolved too late to serve as a transition to Homo, Richmond says.

From top to bottom, A. sediba — represented in the new studies by fossils from a young male and an adult female — possessed traits typical of both Australopithecus and Homo species, Berger’s team contends.

A virtual, 3-D reconstruction of bumps and furrows on the A. sediba male’s brain surface allowed Witwatersrand anthropologist Kristian Carlson and his colleagues to peer through rock and into the male’s skull to measure impressions made by his brain on surrounding bone.

Surface landmarks of A. sediba’s brain look humanlike, although the ancient hominid’s brain is small, even by A. africanus standards, Carlson says. Markers of frontal-brain expansion in A. sediba align it closely with modern humans.

Reorganization of the frontal brain, not a larger overall brain as is often argued, characterized the transition from Australopithecus to Homo, Carlson theorizes.

It’s not yet clear that A. sediba’s frontal brain was more humanlike than that of A. africanus, comments anthropologist Dean Falk of Florida State University in Tallahassee, who was not involved in the research. A. sediba’s reconstructed brain surface includes a frontal landmark found in apes but not people, Falk points out.

Nevertheless, she adds, “I am receptive to the team’s hypothesis that their A. sediba specimens may represent late-surviving members of the lineage that gave direct rise to early Homo.”

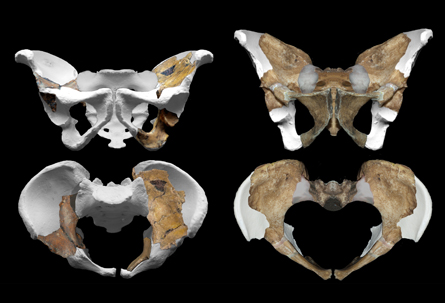

Both A. sediba individuals, and especially the female, possessed bowl-shaped, humanlike hip bones, an unexpected trait for hominids with such small brains, says Witwatersrand anthropologist Job Kibii. This anatomical combination challenges the long-standing idea that wide pelvic openings in the Homo genus evolved in response to brain expansion, allowing females to give birth to babies with relatively big heads, Kibii contends.

Pelvic widening in A. sediba may have evolved in response to an increasing emphasis on walking, he suggests.

Foot, ankle and lower-leg bones from both Malapa individuals underscore that A. sediba walked upright, although more stiffly than modern humans and without abandoning tree climbing, says Witwatersrand anthropologist Bernhard Zipfel.

A nearly complete right hand from the female A. sediba skeleton shows key humanlike features, says anthropologist Tracy Kivell of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. Shortened fingers and a long thumb, as well as evidence of powerful grasping muscles, indicate that A. sediba was capable of making and using stone tools, Kivell says.

In Kivell’s opinion, A. sediba’s hand and wrist were more humanlike than those of the 1.75 million-year-old Homo habilis, which means “handy man.” Stone tools found in 1960 among some of handy man’s remains in East Africa — including parts of a left hand — cemented his reputation as a toolmaker. Researchers have unearthed no stone tools at Malapa.